Each holiday season, I review different modules, games or supplements as a thank you to the wider tabletop roleplaying game community. All of the work I review during Critique Navidad is either given to me by fans of the work or the authors themselves. This holiday season, I hope I can bring attention to a broader range of tabletop roleplaying game work than I usually would be able to, and find things that are new and exciting!

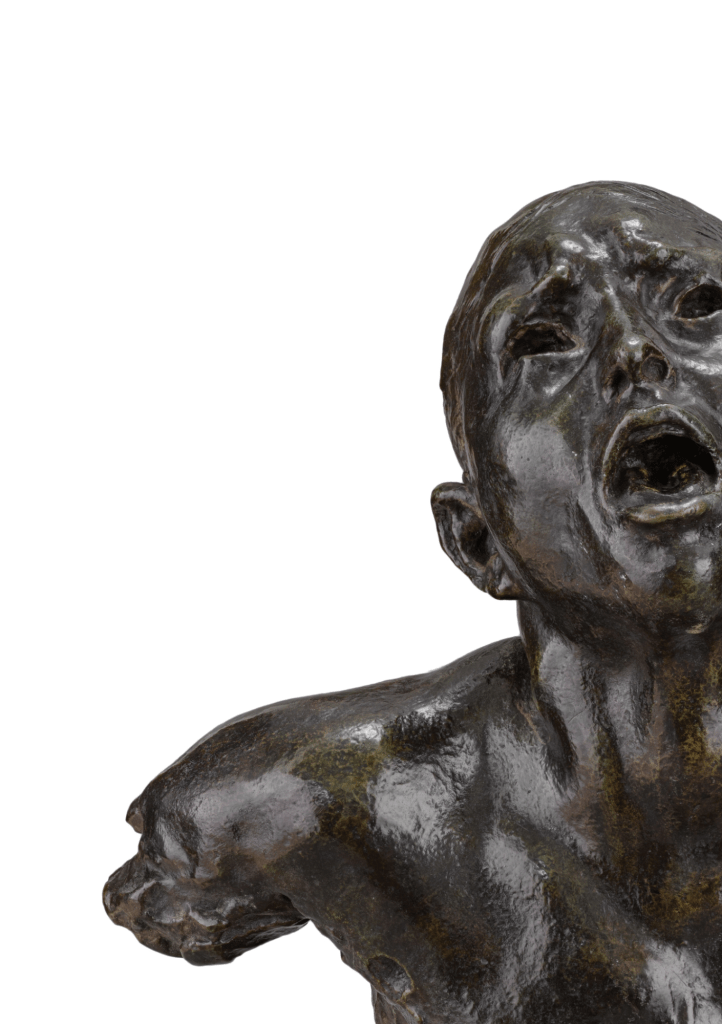

Boy’s Don’t Cry is a 12 page solo game by Markus M. In it, you explore the experiences of growing up as a young cis/het boy between the ages of 10 and 17, with traditionally feminine interests, using the “The Wretched” framework. That framework utilised thusly: Build a tower, draw a card, journal the scene indicated by the car, and pull a block. When the tower falls, the game is over.

Each card in the deck features a scene from your character’s life. The four suits here are horses, fashion and beauty, performance, and romance stories. Many of these scenes are, I think, pretty realistic situations to be in, but I struggle with the writing choices: Namely, there’s a lot of commentary in them: “The guys used to give you a hard time about your pimples. You made the mistake of trying to solve this by putting on concealer, forgetting that to them, make-up is for girls.” I think this commentary misses one purpose of the journalling game, and that’s to imagine and explore the world that’s set up. I could imagine a similar scene: “You are having an acne break out, so you went to the pharmacist to get some pimple cream and concealer. But Theo was there with his mum and he saw!” This leaves what you’re feeling and what the bullies are feeling and how they’re acting there for you to explore yourself. These scenes are iconic; the descriptions over-editorialise, for me. Why is this different to what I spoke about when I reviewed We Three Shall Meet Again a few days ago? I think in this case, every person reading this game already has a very strong foundation to improvise off: Their own childhood. If this was instead set in a world of teenaged dragons, dealing with dragon analogies to dragon gender roles and dragon bullying, I think the additional editorialising would be absolutely essential. But here, you don’t have to explain: Every reader knows what a cat-fight being an adolescent was.

The Wretched has a difficulty toggle — how many cards you draw indicates how “easy” your adolescence is. I find this a very, very strange addition to the game, given it’s essentially an autobiographical game. I also find the metaphor of the Jenga tower to be wanting in this game; if it falls, you choose to conform. I understand the choice, but when you’re choosing a physical act to represent something, I feel it should — for want of a better terminology — feel right. Earlier this month, I reviewed A Stranger’s Just A Friend. The metaphor for sex there was melting a chocolate over a candle. That feels messy, dangerous, and sexual. And messy, dangerous, and sexual was what that game was trying to communicate. A falling Jenga tower does not feel like choosing to confirm; to be honest, I wonder if the opposite metaphor is more apt: Building a wall or a tower, for putting up a mask and changing yourself for others.

This mismatch between physical action (or mechanic) and theme, I think, is a recurring concern I see across a lot of TTPRGs that are based on certain systems or mechanics. Earlier this month, I saw this mismatch in This Mortal Coil. I can see that there’s an appeal in taking something like the Jenga Tower, popularised in TTRPGs in the horror game Dread, and subverting it to mean something else. But in Dread, and in the Wretched and Alone, it is a tension-building mechanism, a metaphor for rising doom. Instead of adopting systems designed for specific purposes, even if the intent is to subvert, we should be considering what feelings we’re trying to evoke and build a game from that. I think, particularly for designers starting out, using a system that you’re familiar with can be a really helpful scaffold to getting design done at all. But I do think that where there’s a mismatch between theme and physical action or mechanic, as designers we playtest the game, meditate on the mismatch, and then consider how we can change our design so that this mismatch is minimised, or at least used for maximum effect.

Boy’s Don’t Cry is an effective journalling game, with some iconic choices of scene that will be familiar to most adults who defied gender stereotypes as children, if not in the specifics, in the generalities. But it does fall apart in its translation of the system it uses to telling that specific story. If you’re interested in spending time exploring your own childhood and your struggles with gender stereotypes and bullying, and honestly, I’m not aware of much else that explores this territory, aside from the autobiographical Logan, which does it from a completely different perspective. If that’s interesting to you, Boy’s Don’t Cry is a good place to start.

Idle Cartulary

Playful Void is a production of Idle Cartulary. If you liked this article, please consider liking, sharing, and subscribing to the Idle Digest Newsletter. If you want to support Idle Cartulary continuing to provide Bathtub Reviews, I Read Reviews, and Dungeon Regular, please consider a one-off donation or becoming a regular supporter of Idle Cartulary on Ko-fi.

Leave a comment