You may have noticed that a common theme in my reviews is that I criticise people’s random tables: Their wilderness generators, their wandering monsters, their weather tables, their treasure tables. Why? Because often I see randomisation misused, particularly when taking the form of a random table. So, I’m going to break down a few of the ways that randomisation can be misused, and a few questions you can ask yourself to identify if you’re using it well. I’m writing this primarily for use in modules, but the principles can be easily generalised to broader TTRPG prep and game design.

Note: I’m numbering these “errors”, not because they have any type of hierarchy, but simply so I can refer back to them at a later stage. Also, I’m certain I’ll have forgotten to include some types of error, so I will come back and update this as I think of more stuff that’s relevant (or if you alert me to something I haven’t thought of that I think belongs here).

What is randomisation for in modules?

Randomisation is almost always a stand in for another, more complex system. If you identify what it’s standing in for, it’ll be easy to see if you’ve made a mistake. Some common things randomisation stands in for include:

- The predictable daily movements of people through a lived in space

- Unpredictable changes in weather conditions or other effects like mutagens

- Knowing what a character you’ve never met before would do

- The nature of a building in a large city

- The infinite potential of a closed container

There are other common uses. One common other use for randomisation where it isn’t a stand in, is where it is used to introduce dramatic tension. For this, the players need to know what the results might be and need to be hoping for a specific one. The obvious example of this is, of course, the to-hit roll which might — just might — score a critical hit. But, that d6 you roll in Old School Essentials to find out if you’re going to have a random encounter? That’s also an example of this. Another common use of randomisation where it isn’t a stand in is in the form of abstract prompts. An example of this is a spread of Dixit cards because they have no intrinsic meaning but instead help you create meaning from nothing. Spark tables are another example of this. These kinds of randomisation don’t really play by the same rules, so these errors don’t apply there.

What about replayability?

A bunch of arguments for committing a bunch of the errors I’m about to list hinge around the fact that committing them might potentially increase the game’s replayability. Your argument is probably right: committing some of these errors may increase replayability. However, I don’t think that the value of that replayability is greater than the cost of the replayability. There are probably more costs than these, but certainly those costs include:

- The verisimilitude of your world being compromised by the wrong things showing up too often, too rarely, or at the wrong times

- Your carefully worded, thought out, and refined results not seeing the play or gravitational affect they deserve in the world you’re writing about

- Referees or players that are less engaged by random tables than you, being turned off by the slow pace of your book, and never engaging with your module

As a referee, I have never experienced giving the same players playing the same characters the same scene twice and seen them acting the same way. There’s so much unpredictability inherent in this hobby, that I just don’t think replayability merits significant consideration when it comes to module design. Your module is probably immensely replayable without your putting any effort into it.

I suggest we focus, instead, on writing excellent tables.

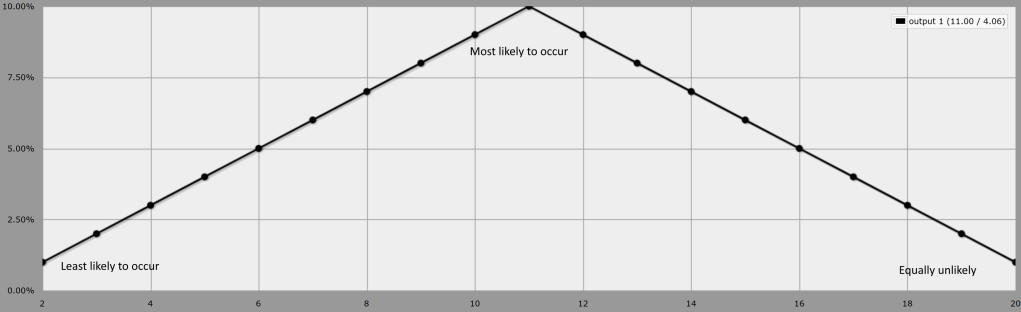

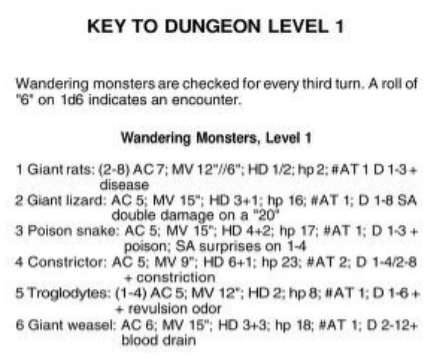

Type 1 Error: Poor choice of distribution

Be intentional about whether you’re utilising a flat or a bell-curved distribution in your randomisation. A brief refresher: If you roll 2 or more dice together, the probability of the numbers in the middle of your available “slots” being rolled are higher than the ones on the edges (the lowest and highest numbers).

So, if you’re choosing to roll 2d6, you need to consider how often things are going to show up — it’s not just a handy way to have 12 items (sic) when you only have d6s to roll. And, if you’re rolling 1d6 it’s important to remember that the 6th option is just as likely to show up as the 1st one.

If you want more information about probability and distribution, I’d check Lyme’s primer or AnyDice’s articles. There are a bunch of advanced techniques you can use, but honestly knowing the difference between a flat and a bell curved distribution will cover most people’s needs.

Ask yourself if some items on this list are more likely to happen than others.

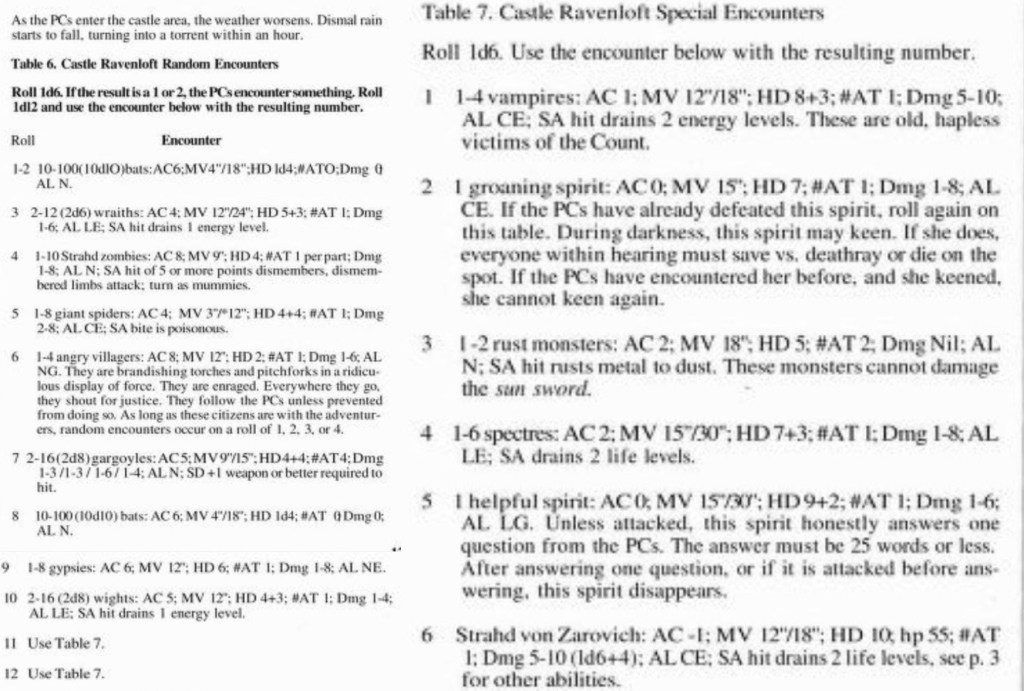

Type 2 Error: Poor choice of governance

A random table has to be specific to when it’s used. If you start using a single table to govern multiple circumstances, you’ll weaken the “power” (for want of a better word) of the random table in the circumstance in which it is used.

In my hypothetical module Dragon-Spearers, random encounters are used when moving around the wilderness, typically for most OSR-style wildernesses. But, in individual keys, it’s also used for filling monster lairs, if the party approaches the decomposing bodies, if you fail to cross the river fast enough, and on certain weather rolls. These circumstances really require their own bespoke tables or specific examples of what might happen. Why would bad weather trigger the same selection of encounters as a monster lair?

If you’re referring to a random table designed for another use, ask yourself if this circumstance warrants its own random table.

Type 3 Error: Poor choice of scope

When you’re building a dungeon with only 6 rooms, having 1d20 random encounters means a bunch of those will never occur in a single play through. If you’re building a dungeon with 30 rooms, having 1d6 random encounters means a bunch of those will recur in a single playthrough. If I’m super-generous and assume 3 rolls per room because the player characters are loud and dilly-dallying, a 6-room dungeon will still see only 12 rolls, and hence most likely only see 2 of your entries.

Basically, I’d suggest trying to intuit what your dungeon needs, and try to match the scope of your tables to the scope of your module, based on the instructions you’re using for rolling on it.

Ask yourself does this random table have insufficient items to satisfy the instructions I’ve given for rolling on it, or does it have too many?

Type 4 Error: Sub- and co-tables

If I have to roll multiple times on different random lists or tables to get a single result, it’s usually boring and time consuming. Almost all tables are better off being a giant array with very specific results, i.e. distributing all of those sub-table rolls into one extra-big table. Don’t forget, we have tons of options for weirdly numbered tables using the d100 method: d44 with 16 results and d88 with 64 results, plus you can combine any two or three dice for a unique number of entries. The reason there’s been a trend towards overloading random tables lately, is to reduce the number of rolls necessary to get results.

Ask yourself if you have a good reason to be asking someone to roll on that second random table.

Type 5 Error: A concrete entry would be better

Intention and context is really important when identifying a type 5 error, which applies almost exclusively to when randomisation is used to generate content. If your wilderness only contains enough space for 3 villages, but you include a wilderness generator with enough information to generator 12 villages, most of the work you’ve done will be wasted at most tables that are playing your game. I strongly recommend in these cases, that you should put your best writing into just making 3 villages. The same goes for random character generators that will only be used once or twice.

In my hypothetical piracy module Black Tath’s Trove, all the islands are generated procedurally, by combining a list of 30 terrains and 30 features, requiring the referee to improvise a new island based on this huge number of potential combinations. However, in my wildest dreams I wouldn’t expect my campaign of the Black Tath’s Trove will last 900 islands, let alone my imagination remain capable of improvising new islands based on these increasingly repetitive combinations. The 30-odd pages I spent on these lists of things to combine to make islands could instead have been a significant number of unique islands based on exactly the same content — at least an isle per page or 30 islands — plenty to sustain any campaign for a decently long time.

Ask yourself what the benefit of this being a random table is, over it being a concrete thing, and weigh that benefit over the benefit of the concrete thing.

Draw the rest of the owl

One final thing before I conclude: I’m assuming through all of this that your baseline random table is a good one. That the writing is excellent. That it’s meaningful in context. That it’s tied into your world. That it’s evocative. If you write a random table that isn’t compelling, it doesn’t matter if you don’t commit any of these errors, your random table will still suck.

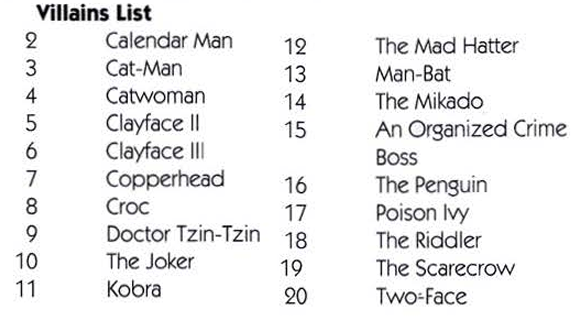

Here I’ve written a random encounter table for a small fortress of about 8 rooms, where some goblins live. Does this random table answer all the questions satisfactorily?

| 2d4 | Encounter |

|---|---|

| 2. | 4 goblins |

| 3. | 3 goblins |

| 4. | 2 goblins |

| 5. | 1 goblin |

| 6. | 2 goblins |

| 7. | 3 goblins |

| 8. | 1 goblin boss, 3 goblins |

- Are items on this list more likely to happen than others?

- What is the benefit of this being a random table, over it being a concrete thing?

- Do you have a good reason to be asking someone to roll on that second random table?

- Does this random table have insufficient or too many items to satisfy the instructions I’ve given for rolling on it?

- Does this circumstance warrant its own random table?

I think it does. It’s just boring, nevertheless. Write more interesting stuff, if you want to fix it. Look for three cumulative features (although you might be looking for other things, based on the context or what you’re randomising):

- Always make your entries evocative in some way (imply things about the world or the characters — all of these items try to do this)

- Often make your entries interconnected in some way (items 2, 5, 6 and 8 all relate specifically to other characters or spaces)

- Occasionally make your entries dynamic (items 2, 6 and 7 change depending on what has happened in other spaces or with other characters, or are impacted by them)

| 2d4 | Encounter |

|---|---|

| 2. | 4 goblins, on patrol, wielding machetes. Their leader, Grug, has a magical whistle which summons the ferret in the walls, to activate the traps in rooms 2, 6, or 5. |

| 3. | 3 goblins, in clothes marked with a shark tooth, playing cards. |

| 4. | 2 goblins, patrolling but deep in conversation. They can be heard in the next room, arguing about whether the latest book in the Black Lotus series is as compelling as the earlier ones. |

| 5. | Hermit, sketching still life. Actually his name’s Kulk, they just call him Hermit because he the other goblins won’t be his friend. They just don’t get art. |

| 6. | Frannie and Herb, being intimate in a corner. If they notice you, they grab their clothes and flee to (5). They aren’t found on a second roll, and instead you find…signs. |

| 7. | 3 goblins, in clothes marked with a shark tooth, practicing machete-fighting with bamboo machetes. It takes a round for them to grab their actual weapons if they’re surprised. |

| 8. | Shark-tooth the Bossblin (from 8), his graft-surgeon (from 9), and 2 guard-gobbos wielding stonefish-tipped clubs. |

The goal here, is to make your random table immediately engaging, even when there are only a few items. Always evocative, often interconnected, occasionally dynamic.

Wrapping up

So, when you write a random table, consider asking yourself these questions:

- What the benefit of this being a random table, over it being a concrete thing? If there isn’t one, or the benefit doesn’t outweigh the cost, replace the random table with a person, place, or thing.

- Are some items on this random table are more likely to happen than others? If yes, consider a curved distribution. If not, consider a flat distribution.

- Does this random table have insufficient items or too many to satisfy the instructions I’ve given for rolling on it? If so, kill some darling entries or write some new ones.

- If you’re referring to a random table designed for another use, does this circumstance warrants its own random table? If it does, write a new one.

- If there are co-tables or sub-tables, do you have a good reason to be asking someone to roll on that second random table? If not, shake and combine.

Of course all of this is awfully subjective, depending on the context of your module, your intent as the author, and a ton of other things. Being able to use randomisation effectively in your modules is but one tool I’m hoping to add to your toolbox. I hope you find a place to use it.

Happy randomising!

Idle Cartulary

Playful Void is a production of Idle Cartulary. If you liked this article, please consider liking, sharing, and subscribing to the Idle Digest Newsletter. If you want to support Idle Cartulary continuing to provide Bathtub Reviews, I Read Reviews, and Dungeon Regular, please consider a one-off donation or becoming a regular supporter of Idle Cartulary on Ko-fi.

Leave a comment