Make Dice Work For You is a series where I’ll regularly talk through a new way to use dice in your game. It came out of conversation surrounding What to randomise when you’re randomising, and what advanced techniques you can use for specific needs. I’ll where I know, but please help me out if you know a citation and I don’t have one, or if you know an example that I can add!

So, you want to have a list where all the items are equally likely to be chosen. Some obvious answers:

- 1d4 has 4 options

- 1d6 has 6 options

- 1d8 has 8 options

- 1d10 has 10 options

- 1d12 has 12options

- 1d20 has 20 options

If you’re willing to assume the person rolling your list has zocchi dice, you can also use lists of 3, 5, 14, 16, 24 and 30 as well, all by rolling a single die. If you roll any 2 dice and add them, however, you get a bell curve — the list is no longer equal opportunity. Can you combine 2 dice without a bell curve?

Yes, you can, by taking the face value of each die, and assigning them to a set of digits, usually tens and ones. This is how the percentile die in your dice set works. All you need is pre-determined order — one dice is always used for the tens column and the other always for the ones column for this to work; most commonly this is determined by colour or by order of rolling. We tend to call these “dXX” where the XX is the highest possible value you can roll, but one quirk is that that number won’t be the total number of options, but rather those two digits multiplied together will be the number of items available for your list.

Some bvious choices:

- d44 has 16 options

- d66 has 36 options

- d88 has 64 options

- d100 has 100 options; we’d always prefer these dice labeled 0-9 for these purposes.

- Using the d12, d14, d16, d20 and d24 in this way is possible, but the math isn’t as intuitive for average audiences.

Note: Evidencing this in Anydice makes for some really boring graphs, but this is the formula for the script to price that the curve is flat for any of these rolls so long as they are ordered: output dN*10+dN, where N is the die size.

Less obviously, you can combine different sized dice for other sized lists. These can be more intuitive, because it’s easier to remember which die is tens and which is ones to preserve order (which, remember, is essential for these tales to work):

- d46 and d64 have 24 options

- d48 and d84 have 32 options

- d410 and d104 have 40 options

- d68 and d86 have 48 options

- d610 and d106 have 60 options

- d810 and d108 have 80 options

So, we have 19 options between 4 and 100 to easily write a list without preference in terms of probability. Cool.

Note: To evidence these in Anydice, simply output dN*10+dM, where N and M are the die size.

The astute among you realise that this works for any set of digits: You could do it for hundreds, tens, and ones, or even thousands, hundreds, tens and ones. Yes, you could, but these rapidly get unwieldy. If you needed a very big but unusual sized table, you’d probably want to put smaller dice sizes up first in the reading order, because the numbers get very big very fast, and having many dice of the same type make it harder to preserve order:

- d444 has 64 options

- d666 has 216 options

- d4444 has 256 options

- d6666 has 1296 options

- d8888 has 4096 options

Note: To evidence these in Anydice, simply output dK*1000+dL*100+dM*10+dN, where K, L, M and N are the die sizes.

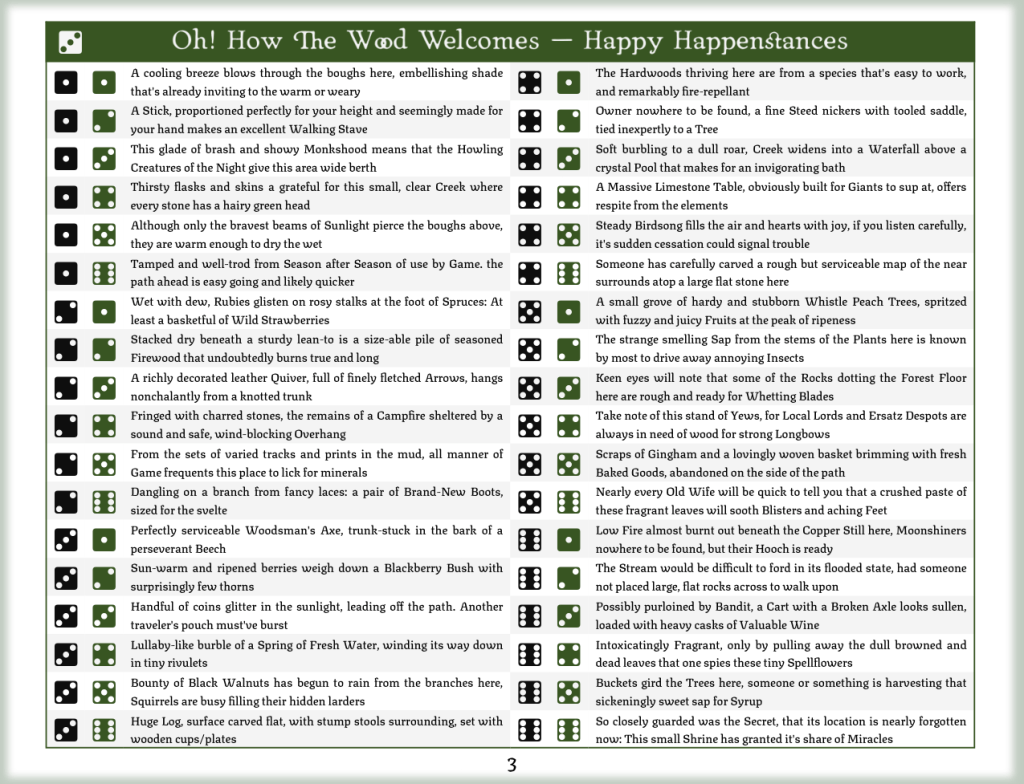

Personally, I don’t see much of a use case for these complex flat distributions, but there is one: The larger your flat number, the more chance there is for secondary features. You could assign special stacking conditions to doubles, triples, or quadruples, for example. A random encounter table for a city of 256 characters, who’ll try to sell you something on doubles, act suspicious on triples, and hostile or steal from you on quadruples might be a good way to use this. If you assigned wide ranges to results, you could get these benefits without hundreds of entries, and you could manage probability closely too if you wanted to do some math, for a more labour intensive probability curve that favoured certain results. The precise probabilities of doubles get messy, and are unique for each set of dice, although as a rule of thumb I think doubles are more likely with smaller dice, and I think that likelihood is about 1-in-N for doubles, 1-in-N^2 for triples and 1-in-N^3 for quadruples. An example of these kind of secondary features (which Prismatic Wasteland popularised as “overloading”) is in Zzarchov’s Lost in the Wilderness:

Note: If any Anydice wizards know how to generate precise probabilities for doubles and triples in a 3-dice set, please let me know and I’ll include your work or a link to it in this post as evidence here, or amend the above.

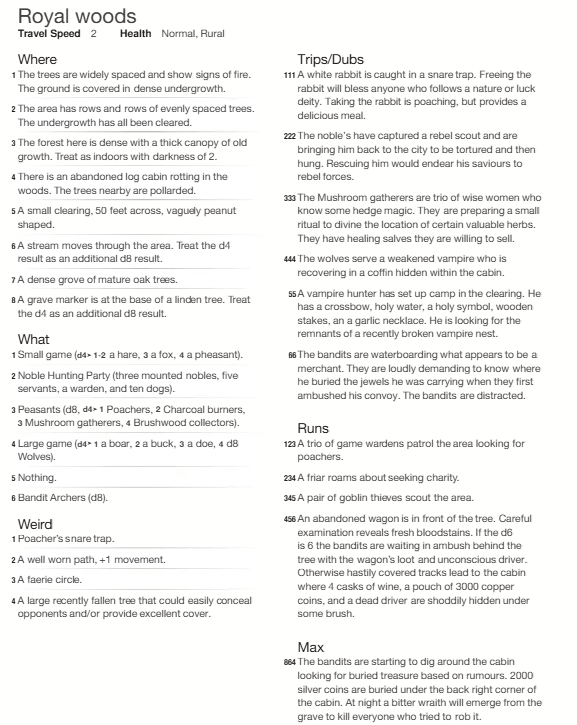

Ok, I don’t think I need to give an example of how to use a flat list, but just to clarify what the numbering would look like, for a d44 table for example, the leg hand column would be: 11, 12, 13, 14, 21, 22, 23, 24, 31, 32, 33, 34, 41, 42, 43, 44, for a total of 16 entries. Here’s an example of a d66 table from Forest Farragoes by kTrey of d4caltrops:

You can see how colour is used to preserve order, and how numbering isn’t from 1 to 36 despite there being 36 item.

A final note for those looking for complexity: If you decide to add advantage to these rolls (i.e. roll 3, take the highest 2 results, in order), you introduce a probability curve to the list. I think this is a bad idea, personally, because to me the elegance of these tables is the flat probability at high numbers. But if you’re looking for something very specific, it might suit your need. Goblin’s Henchmen talks about the implications of that here.

To summarise, Equal Opportunity Dice:

Basic Structure: Roll multiple dice, preserving order, with each result resulting either hundreds, tens, or ones.

Effect: A list of items where there is equal chance for any to occur, at a very flexible number of list results.

Requirements: Roll order must be preserved so that a single die equates to tens, and another to ones, and you cannot roll more dice and then drop the highest or lowest or the probability will change for each item.

Alternatives: You can add additional information to doubles, triples and quadruples without impacting the probability of a given list item occurring.

Idle Cartulary

Playful Void is a production of Idle Cartulary. If you liked this article, please consider liking, sharing, and subscribing to the Idle Digest Newsletter. If you want to support Idle Cartulary continuing to provide Bathtub Reviews, I Read Reviews, and other work, please consider a one-off donation or becoming a regular supporter of Idle Cartulary on Ko-fi.

Leave a comment