Over on Prismatic Wasteland, we have a very cool way to roll just 3d6 to tell you what monster, how many monsters, the distance they’re at, their reaction, and whether the players are surprised by this all. It’s elegant as heck at the front end, and takes advantage of the power of 3d6, but because using 3d6 causes every value to become a dependent variable, it is messy as heck at the back end, requiring a worksheet and an extended example to make work.

Now, to be pretty damned clear, dependent variables can lead to interesting overall results, particularly in this case where if you use a variation on “advantage” for increasingly dangerous areas, you’ll get higher numbers and more dangerous results. And having these specific requirements for a random encounter table might actually inspire you to more interesting writing. However, for me, I don’t want to have to put this much thought into the positions on my random encounter table.

I have a few problems with the specific results here too, particularly that only about 5% of results are surprise results, versus about 17% in B/X. This just seems like less fun, I like surprises. This has a positive dependency in it though: surprises are always at close range.

Of course, the “problem” (if it is such a thing) of dependency is pretty straightforwardly solved: Firstly but simply using 3 different coloured dice rather than ones that are indistinguishable from each other. But this is both (a) annoying to non-colour blind players and (b) not an accessible tool for colour-blind players.

But an easier solution is simply to use different sized dice. This is analogous to rolling on 3 different tables simultaneously, yes, but so is the original exploding random encounter table, to be honest, you’re just not differentiating which dice rolls on which of your tables.

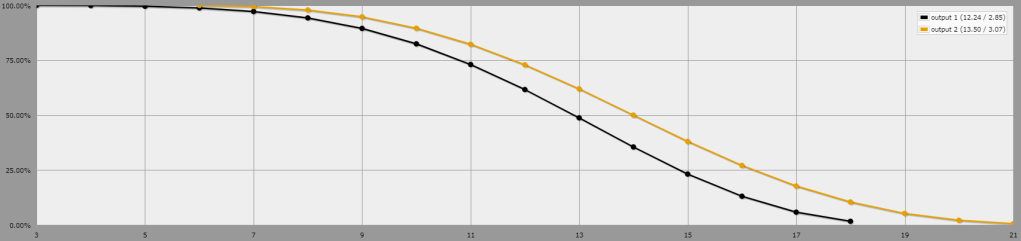

Quickly with probability differences. Switching to 1d4+1d6+1d8 (Jonathan Korman called this d468 on twitter and I’ll take it) gives a slightly softer curve. The chance of doubles on 3d6 is about 33%, and of triples is 5%. The chance of doubles on d468 is about 42%, and of triples is about 2%.

We can’t explode the d468 die, sadly. It has a very neat weighted danger curve. However, adding 3 to the result gives us this slightly more dangerous overall curve:

The Rule

Write a table with results labelled from 3 to 18. The d4 indicates the number of monsters in the encounter. The d6 indicates the distance of the encounter. The d8 indicates monsters reaction. On doubles, the player character’s gain initiative. On triples, roll again: Two random encounters are already engaged with each other.

In the table results, indicate whether the monsters are in a small, medium or large group, and double or triple your d4 result accordingly. If an encounter result is a specified as a single monster, the d4 can be used to indicate their behaviour. If an area is more dangerous, add 1 to each die (and hence 3 to the overall result).

The Generic Template

| d4: # | d6: Distance | d8: Reaction | |

| 1 | 1/2/3 | Far | Actively friendly |

| 2 | 2/4/6 | Far | Curious and open to cooperation |

| 3 | 3/6/9 | Far | Curious and open to cooperation |

| 4 | 4/8/12 | Close | Bargain or parley |

| 5 | – | Close | Bargain or parley |

| 6 | – | Surprised | May attack if victory is likely |

| 7 | – | – | May attack if victory is likely |

| 8 | – | – | Offended or disgusted |

This gives us a dependency-free version of the original overloaded random encounter table. This incorporates side-based initiative at a slightly higher rate than the original 50% (rather than individual and dex-modified, which was optional in B/X). It gives us a chance of multiple encounters concurrently. The only necessary rule to remember is that more dangerous things should go at the bottom of the table, so that the increased danger works.

I’d say similarly elegant at the front end, with a lot less math at the back end. I can’t be stuffed writing an example table after all that, so I’ll just copy and modify Prismatic Wasteland’s:

3 — Small number of escaped human prisoners from the nearby village

4 — Small number of emaciated dwarves scrubbing orcish graffiti from the walls

5 — A forbidden orc and dwarf lovers fleeing from their families

6 — An animated dining room set restlessly rearranging itself (# appearing is highest die)

7 — A wise troglodyte admiring their treasure, a dwarf-crafted weapon

8 — Medium number of troglodytes gleefully dragging a fresh orc corpse

9 — An ooze that disguises itself as a puddle of putrid liquid

10 — An orc shaman looking for: (1) someone who can teach her a new spell, (2) fresh, wriggling ingredients for a stew, (3) a worthy puppet to overthrow her former ogre-puppet who has become unruly, (4) her kissing snake-kitten

11 — Orc warriors that are (consult lowest die): (1) grumbling about their ogre of a boss, (2) carrying a wounded ally, (3) taking turns boasting over martial accomplishments (# appearing is double the median die)

12 — A sentient stalagmite-beast with tentacles, needle teeth and a single eye, that appears as a simple stalagmite

13 — An ogre warlord playing fetch with his small number of pet dire wolves

14 — A giant worm-beast whose face peels open like a banana to reveal sharp pincers

15 — A pile of bones knitting together to form a large number of animated skeletons of orc warriors

16 — A young black dragon, searching for materials to add to its burgeoning hoard

17 — The wraith of a dwarf mage wracked with crippling guilt and consumed with anger

18 — A demon that wants to possess the body of an innocent looking outsider so it can escape into the surface world and wreak havoc in a populated haven

Notes on the above table: I’ve already been writing this post for a while and wanted to move on to other things, so it’s definitely all straight up Prismatic Wasteland’s with a few small changes. If it were mine, I’d do these things: All the individual monsters would have 4 unique behaviours. I didn’t order things at all except for putting deadlier and rare things higher, and less deadly and rarer things early, with more common things in the middle.

Anyway that’s my double-overloaded random encounter table. Even more overloaded, but with even fewer dependencies, and only really one probability concession.

Idle Cartulary

Playful Void is a production of Idle Cartulary. If you liked this article, please consider liking, sharing, and subscribing to the Idle Digest Newsletter. If you want to support Idle Cartulary continuing to provide Bathtub Reviews, I Read Reviews, and Dungeon Regular, please consider a one-off donation or becoming a regular supporter of Idle Cartulary on Ko-fi.