Bathtub Reviews are an excuse for me to read modules a little more closely. I’m doing them to critique a wide range of modules from the perspective of my own table and to learn for my own module design. They’re stream of consciousness and unedited critiques. I’m writing them on my phone in the bath.

This is a special Bathtub Review: I’m going to read Keep on the Borderlands, and compare and contrast it with two modern reimaginings, Beyond the Borderlands and Bastion on the Frontier. Why? It’s my 50th Bathtub Review, and so I thought something special like reviewing a classic module was in order. There were a lot of other takes on the material out there (thanks to everyone who helped out on Discord to suggest them), but on first pass I felt these two and the original would yield the most fruitful discussion. I picked them based on a quick read and their contrasting approaches, but surprisingly they shared some creators despite this.

Keep on the Borderlands is a 26 page module for Basic D&D by Gary Gygax. It is sparsely illustrated and features some incoherent maps. It is also one of the most iconic modules in the history of the hobby. Keep on the Borderlands is a blank slate of a module at best, and a bad module at worst: A hyperdense, poorly written, incoherent module that is nevertheless inchoate of everything that followed it. It’s not exactly fair to judge something written in 1981 based on my modern sensibilities, but in short it is poorly laid out, terribly mapped and minimally illustrated, though in the pleasingly janky style of the time. Let’s focus in on the interesting and good parts: It’s designed for a party of nine players. The rumour table could be shortened to be more interesting, but most rumours, false and true, refer to specific encounters. In the context of such a big rumour table (20 rumours!), it seems you’re supposed to hand them out like candy, which I like. The Keep itself is over-keyed, and with no personality given to any character despite this; NPCs encountered are supposed to be randomly generated with a perfectly adequate procedure in the back of the module. These aren’t bad, though: A friendly but wasteful ally is actually a nice archetype, for example, but I’d prefer the NPCs be actually described. The Keep is supposed to be a living, breathing place, and with a bit of effort it is. Everything is there: You just need to put all the disparate pieces together.

The Keep is designed to be looted, and tough penalties are in place to those who are caught; as Prismatic noted, it’s a weirdly fascistic little society that really begs to be interpreted as a place where the law is maladaptive. The lack of interrelationship means the NPCs feel often robotic, and that those that aren’t part of the failing military apparatus feel like they have something to hide, even though only one is actually described as having a dark secret.

The overland travel is anemic, largely because while the rumours point you to encounters out there, the encounters themselves are on the face of it uninteresting. I’d want the lizard-folk, lion-hermit and brigands to be connected to the Caves of Chaos in some way, for them to have value in the interplay. It should be noted that there is a 1-in-20 chance of linking these in through random encounters, if the referee is quick on their feet. There is an implication that that shrine that turns people evil is the reason there is a traitor in the keep, but it’s the most subtle of hints.

In the Caves themselves, faction play is encouraged in theory (a single sentence, really), but no goals are provided beyond “warring monsters”, and so truly playing chaos politics isn’t possible without adding a lot of context. Basically there are six warring tribes down here, with a few unique powerful monsters that feature on their own. This is ripe for interaction, with a little supplementation. But Gygax wants us to know that chaos is evil, in the few descriptions he provides still cast the foes as evil: “something evil is watching”, the bugbears are slavers, the gnolls mercenaries. I’m not going to spend time going into the particular problems with the themes in Keep of the Borderlands, in my opinion it’s an overdone topic, but recently RTFM expounded it at length, so go listen to that. I don’t care to argue them, but effectively the play style here was described well by KTrey of d4Caltrops: “Room to Room, Hack and Slash, Retreats to the Keep to Recruit new Characters when ones would fall or to trade for supplies/better Armor/Weapons.” While technically the tools for interesting faction play are here, it’s designed as a genocide simulator that only works if the denizens of the caves deserve death. That said, if you wanted to write this up with battle maps for 4th edition or Pathfinder 2 or Icon, this genocide simulator would actually be a interesting, multipronged campaign with the potential for a lot of superheroic fun. As a B/X module, though, it leaves a lot to be desired, especially by modern standards.

This review, then, will explore what a fine line there is between genocide simulator and compelling sandbox. From a design perspective, all I’m really left wanting to add to the Keep in the Borderlands is character descriptions, relationships and faction goals. Practically, I’d link things together in ways that make clear the connections (if, indeed, the connections are intentional). Thematically, leaning into the who of all the people and factions and eliminating the evil chaos removes the genocide simulator aspect. Everything else is surprisingly adequate for play. This is a very dense dungeon with a lot of factions supported by more surface factions and a potentially complex home base. I just want sometime to capitalise on that providing what is missing.

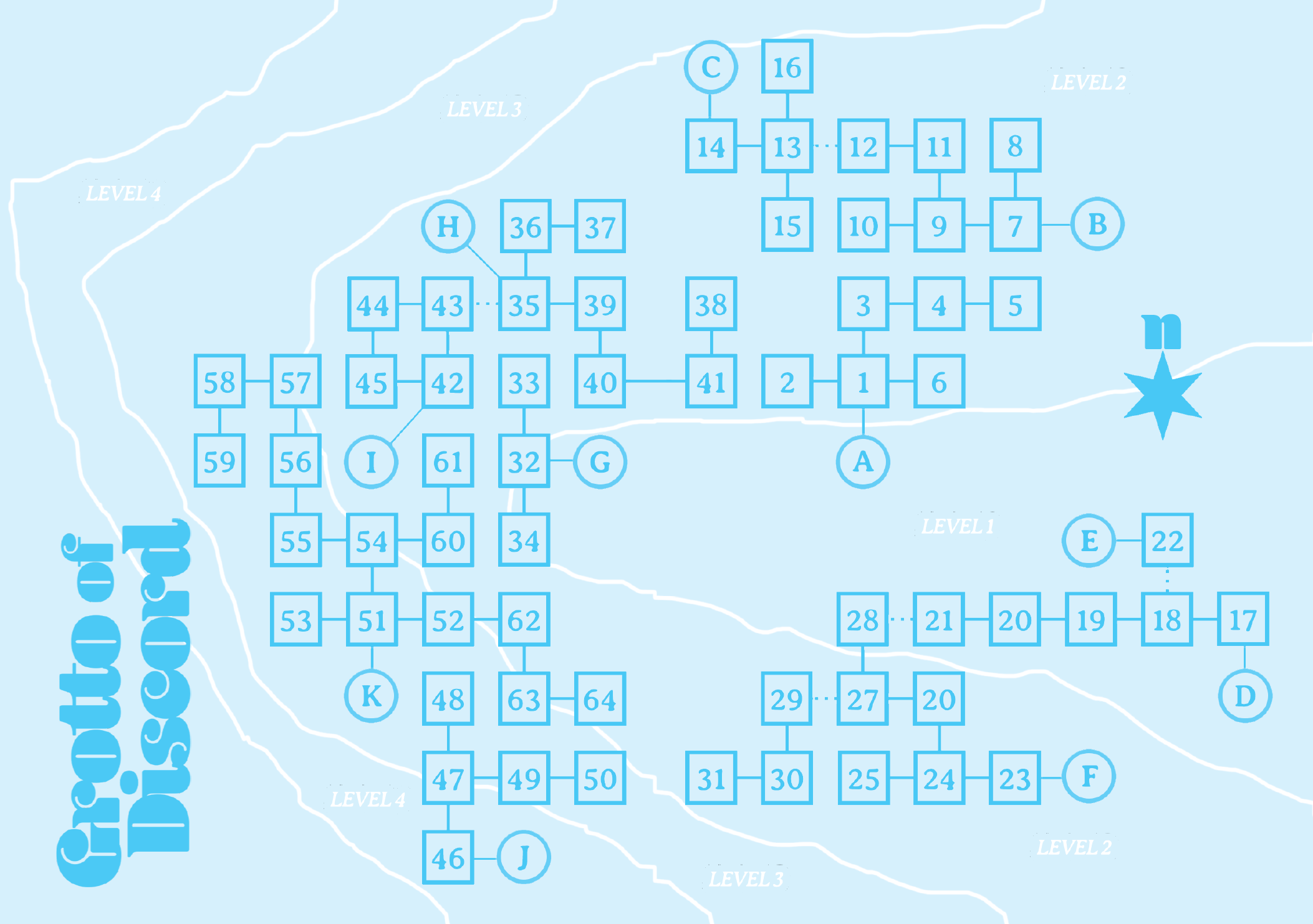

Enter Bastion on the Frontier. Branded a “Bastardized Classic” and released for free as advertisement for the series, it’s written by Jon Davis who wrote the excellent A Tower Darkly, Alex Demaceno who wrote the three-part Beyond the Borderlands that I’ll talk about a little later, and Micah Anderson who wrote Bastards but is better known for their sparse and stylish layouts. Ostentatiously and thoughtfully laid out by Matthew Morris (behind exceptional module “What lies within the pools…”), it nevertheless falls short on presentation despite its clever touches: I despise the node-mapped dungeons which are nigh illegible, despite their clever depth mapping. The bold 70’s themes font choices are both anachronistic in their reference and difficult text to read at a brush. Even the standard, slightly bold serif used often sports less than 30 characters per line, and often twenty, causing font sizes to swing wildly between pages. I like that the “warring tribes” of the caves are summarised to usually single pages, although the faintly backgrounded room numbers add another level of illegibility to using these practically. Even the stat blocks are at right angles to the rest of the text. It’s an exercise in form over function that is really disappointing.

The true travesty of Bastion on the Frontier, for me, though, is that it doesn’t add much any of the things I wished were added to the original. The things that make it more runnable are decidedly absent, and in their place superficial changes such as the lizard-men becoming lungfish-folk, or the Hermit becoming an insane druid with a puma. These superficial changes stand out all the more when the rumour table is almost identical, and when the authors seize upon but do not reinterpret the few strong iconic moments in this, such as the goblin cry “Bree-yark”.

The main innovation of Bastion on the Frontier, to be honest, is its brevity. The ponderous, over-keyed monstrosity of Keep on the Borderlands becomes much more readable in brief, but that brevity doesn’t bring with it a consistent strength in every key; it often becomes “4d6 guardsmen”, or preserves Gygax’s strange predisposition with “3 males, 5 females, and 9 kids”. There are a few neat touches added to the original, and a few nice evocative flourishes — a “bloodthirsty ape-beast” here, “rats in the walls, whispers in the night” there. Not enough to make this compelling, though. It lays bare some of the implications in the original in a way that I feel is useful (the princess is a Gorgon!), rather than the weirdly opaque original that rewards multiple readthroughs of dry and dreary High Gygaxian. The Forgotten Caverns are an absurdity that I’d be embarrassed if anyone had asked to pay for: “Here’s a dungeon with no map, key it yourself” is the absolute dregs of module design, I’m sorry.

The problem, however, is that it doesn’t really remove the genocide simulator aspect of the original at all. The foray into “bastardization” here feels like either a cursory phone-in to drum up interest in the series of classic reimaginings (it’s a failure, for me, I wouldn’t look any further) or so unwilling to engage with its subject matter I question its value as a response at all. It doesn’t feel entirely uncritical, just only willing to excise and not willing to actively respond. Does that make it worth it? Well, it’s free. It’s probably more usable than the original for many modern styles of play, due to its brevity. But is it good? No, it’s not good either, it’s just less impenetrable and has marginally more personality.

Alex Damaceno, who wrote the Caves of Chaos conversion for Bastion on the Frontier, first wrote the lengthy, three part, fully illustrated Beyond the Borderlands. The polar opposite in presentation than Bastion, it is densely illustrated, explains itself at length, has amateurish layout, and is full of personality. It has all the hallmarks of a project that grew in the making, with the earlier issues projecting items that never came to be, or came to be out of order. It’s garishly coloured, it’s sumptuously written, and it doesn’t ape Keep on the Borderlands as Bastion on the Frontier does, but rather builds on it. It feels the work of an artist who tried to run the original, and produced this in the process.

There are relationships between the characters in the Keep, and they get descriptions, if simple ones. These are stereotypes, but they work. The rumours become a notice board, which while not being quite as powerful as the original, is definitely more flavourful and has provides more active encouragement to engage with the world at large.The fascism of the keep is attributed to a religious order, and in doing so, the colonialist wild west of the original is transmuted into the crusades of the middle ages in a compelling way. The borderlands themselves are expanded upon in beautiful and thorough manner. Everything in the overland travel section of the original Keep is expanded upon in interesting manner.

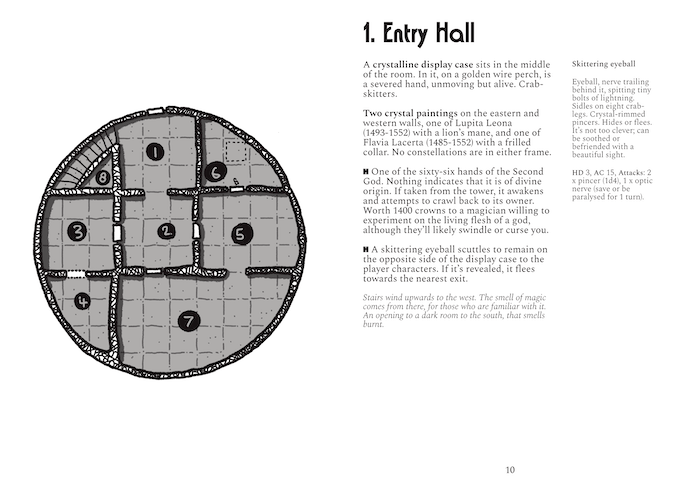

The underworld itself, isn’t quite as strong as the overworld, although it’s just as beautiful. Damacino’s style lends itself to small, intricately detailed spaces, and so the sprawling unknowability of the Caves of Chaos are lost here to a cutesy and structured grouping of underground dwellings. This, combined with the simple but homey writing, humanises the inhabitants of the caves in a way that, to me, seems an intentional follow-through of the crusader-keep above ground. Even Damacino’s undead have feelings and don’t want to be disturbed; the monsters have character traits ( an earth elemental is “Barly’s loyal friend, deeply introspective“).

I hoped the third issue would expand upon the compelling, growing response in this to the violent, fascist and colonialist themes in the original, but sadly it doesn’t, and instead is the weakest entry out of the three, not because it doesn’t expand the world, but rather because it doesn’t preserve any of the characterisation that came in the first two issues. It’s a very mechanical, randomly generated dungeon, that brings a lot of gonzo fun, but none of the interesting and compelling characters. But in general, the genocide simulator of the original has been replaced with a compelling theocratic religious state in opposition to friendly and compelling indigenous folk, in a way that would make for a far more interesting and engaging campaign than the original, despite my wishes to lean into this interpretation with a lot more weight.

It’s a sadness that the beautiful art and compelling writing isn’t supported by a stronger layout. It’s often difficult to read, the headings and bullets aren’t strong and the decorative font choices are a little too decorative. I’d love to see that when this is released inevitably as a book (and it deserves to be!) that it be gifted with a solid developmental edit and a full layout so it can achieve its full potential.

Looking at all three of these, what’s most worth commenting are both the contrasting approaches to the appearance of each of the derivative works, as well as the contrasting approaches to the themes. Keep on the Borderlands has an explicitly fascistic keep and an evil, othered Caves of Chaos. You are expected to slaughter every “male, female and child” in the place. Bastion chooses to excise the themes rather than respond to them; the Bastion is no longer fascistic, but lacks any overall personality. The inhabitants of the Grotto are no longer portrayed as explicitly evil and worthy of death, but they aren’t de-othered, but left as blank slates. In something based on something that is largely a blank slate, it renders Bastion on the Frontier both a pointless endeavor and an easier option to bring to the table. Beyond the Borderlands, reinterprets the themes, making the fascistic keep a theocracy, crusading upon a land full of “monsters” that are, in fact, personable, kind, and largely want to be left alone. It doesn’t explicitly reverse the power dynamic, but in play it will implicitly do so, and likely would fill the campaign with both whimsy and moral dilemmas.

Are any of these three good, or perfect? Keep on the Borderlands is not good, but not without its sheen. If you actively attempt to engage with its flaws, like its fascistic keep and its genocide simulator caves, it’s not an unusuable module, although I’d question whether it’s worth the effort. Bastion on the Frontier feels either cursory or unwilling to engage with its subject matter, especially given the talent involved. Beyond the Borderlands is good, in my opinion, although it needs to be a little stronger to get a strong recommendation. Factions are still not expounded, character linkages are still weak, connections between places and people are still lacking. I would like to see a version of Beyond the Borderlands that feels actually complete, as both a response to the themes in the original Keep on the Borderlands, and as something that provides compelling play in and of itself. A solid revision of Beyond the Borderlands would approach this, I think, especially if it leant into its implicit theming; in the mean time, it’s a strong contender if you have to bring a classic to the table.

Idle Cartulary

P.S. What classic modules would you like to see me review and compare to their modern counterparts? This was obviously a more time consuming endeavour than the average Bathtub Review, but if you have any favourite reimaginings, please let me know in the comments and I can start preparing for my 100th review!

Playful Void is a production of Idle Cartulary. If you liked this article, please consider liking, sharing, and subscribing to the Idle Digest Newsletter. If you want to support Idle Cartulary continuing to provide Bathtub Reviews, I Read Reviews, and Dungeon Regular, please consider a one-off donation or becoming a regular supporter of Idle Cartulary on Ko-fi.