I Read Games reviews are me reading games when I have nothing better to do, like read a module or write or play a game. I don’t seriously believe that I can judge a game without playing it, usually a lot, so I don’t take these very seriously. But I can talk about its choices and whether or not it gets me excited about bringing it to the table.

Edit, 24th January 2024: This post was nominated for a Bloggie award! Thank you for all your support everyone!

I was going to go to the beach today, but there’s a cyclone or something and the weather is miserable, so instead I read Cloud Empress. It was on my list mainly because I was talking to Sam about my review of Beecher’s Bibles, and was asked the question “Do Mothership fans like the system enough to follow it to other settings or is that community ultimately more about the settings/vibes than the specifics of the rules?” and I thought that was interesting, and Cloud Empress is about the opposite approach to a Panic Engine game to Beecher’s Bibles, to be entirely honest.

You see, Cloud Empress isn’t just a rulebook based on the Panic Engine, it’s also got a companion setting book, and it has seven additional short zines that detail specific locations beyond what’s in the setting book. If what Mothership fans like about Mothership is that there’s a lot of content available for it, Cloud Empress is off to a resounding start. It makes this a difficult review, though. I said I was going to the beach, but honestly It’ll probably take me a few days to read all of this and write about them, so I’m going to take my time, and review the entirety of Cloud Empress, because honestly why make nine zines when you could have just released a book? That’s Watt’s first mistake, to be entirely honest. This should’ve been a chonky hardcover book.

Oh, I should start more formally. Cloud Empress is an ecological science-fantasy setting, reminiscent (to me) of Nausicca and Mononoke, mostly written by Watt (with a star-studded cast of guest writers and additional developers), fully illustrated in absolutely excellent form. The core two books are 60 A5 pages long each, and all seven modules total about the same, so it’s an ambitious project, and as I said above, honestly it should’ve been a chonky hardcover, and I’d hold off until Watt releases it as a deluxe edition because these different documents I find a little difficult to wrap my head around. Like, at least release it as three books?

Enough about that particular complaint, anyway. To the first of the nine books: The Rulebook. Watt is a lovely writer, who adopts the voice of a grandmother telling her people’s story to the younglings. It’s wordy, though, and I immediately bounce off the density of the text, and the floridness of the word choice. It’s well-written, but it’s definitely not for me. In the rulebook, this prose text doesn’t play a huge part in the delivery, and to perhaps the text’s detriment, my eyes tend to skip over it. I need this delivered in bite-sized pieces, scattered through the rules and in its tables, rather than where it’s delivered in page-long (or to be fair, half-page long with art) chunks. It’s also organised a little unintuitively: You don’t find out what chalk is until after you have to decide if you need to take the “Chalk Collecting” skill. But I definitely don’t begrudge the time spent on this unique world and its unique terminology. The vibes here are immaculate, right down to the borders on the character sheet.

The character creation rules seem equally inspired by Into the Odd’s backgrounds as they are by the original mothership rules, with less focus on skills (no skill tree, just a skill list) and more on gear and sparks for roleplay. The skill list itself has a few entries that speak to the uniqueness of the world (“chalk collecting”, “thopter piloting”), but some that while they do do that, may be of limited use from first impressions (“Farmwork”, “Needlework”). In most players, with the background of deadliness we’re inheriting from Mothership, I wonder if anyone would choose the latter over “Spell casting” or “Firearms”, despite what it says about the world.

The basic rules feature little deviation from what you’d expect from an adaptation of the Panic Engine (although, and I’m not sure if this is a feature of timing or something else, it’s not called a Panic Engine system but rather a Mothership hack). There are a few additions that do shed light on the intentions of the world: Rest, for example suggests tasty meals or heartfelt conversation. There are weird magical mushroom spores. There are spells that are very weird in a perfect way related to the fact that they’re closely related in theme to the magical bug corpses that litter the landscape. Magical items (“crests“) are the stolen and broken remains of ancient civilizations architecture. The biggest deviation (again, seemingly seeking inspiration from Into The Odd) is that “most attacks auto-hit”. You only roll an attack if it’s difficult, as do your foes, so there’s a lot of implication that you’re supposed to be clever with combat so that you deal a bunch of damage very quickly for free and they have to roll their dice. Again, there’s good flavour here, though: All weapons are dual use, because this world is not a one of violence. I love the equipment lists which are full of flavour but with very few elucidations. Great fuel for imagination, as are the “What Do You Find” tables. Before I move onto the next book, I’m left feeling like the rules would have been best simplified to a few pages, and the flavour been transferred to the next book, as this feels like it would be a messy reference at the table; but the rules are simple and who doesn’t know how to play Mothership? I could do it from memory. We shall see.

My first impression of the setting book is the inside cover, a big whopping impressive hex map that is rendered as a 16 bit video game map and that…honestly it’s incredibly jarring. The amount of money spent on the art in these books, and they couldn’t have splurged for an illustrated map? Really disappointing, and completely out of left field design wise, in a series of books that is otherwise has an incredibly coherent design direction. The map itself works, and is full of relevant information on the different areas, travel and trade. The rules for the hexcrawl are in this book, rather than in the other. I suspect that from a readability perspective, I’d expect to have these two zines at the table, and so I’d want the rules for travel in the rule book on my left, and the setting details on my right in a separate book. They were released simultaneously (relatively) for me, so I don’t see benefit in separating these out. The rules are fine, and the map is useful. That’s nice. I’ll reset my expectations going into the book proper.

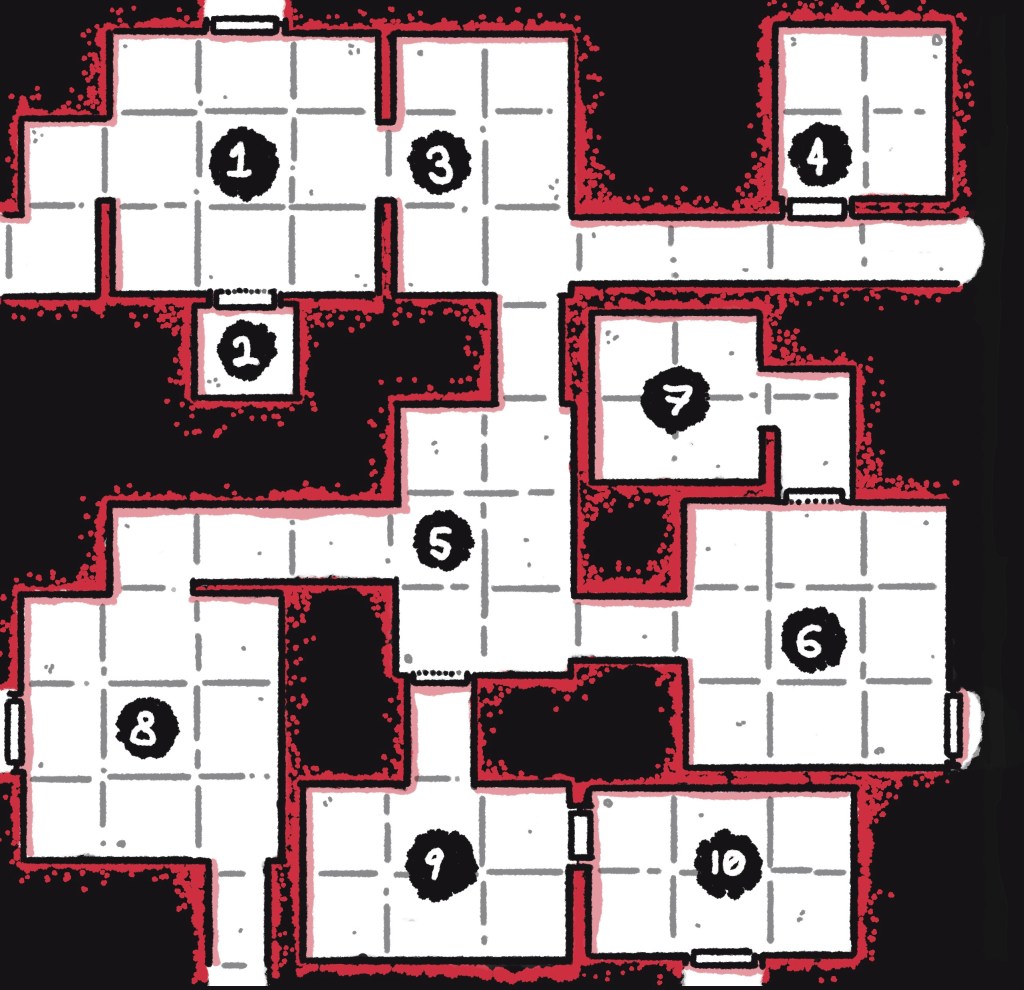

We have a few different regions, each with a Hunt & Gather table, encounters (some with expanded descriptions), unique NPCs, brief 1 paragraph hex descriptions, and then a few specific fully keyed locations (again in that jarring 16 bit map style, which I’m suspecting now was a conscious choice but in my opinion it’s a bad one). So much of this book’s writing is absolute fire, even the merchant generators (which give you a nice single word description of each merchant, plus what they have), and the mood table (which is an interesting take on the reaction table). There’s even a rumour table, although it’s not the most magnetic take on the rumour table; it ranges from clear hooks “Sleepy Renault will give a crest to anyone who brings him the Farmerling pirates on the Broken Back river” to very vague ones that don’t provide much guidance, “There must be a Flesh-thresher repair depot“. I genuinely love most of this.

The layout is very clear in terms of finding what you want, when you want it, and the art (apart from the maps that I shan’t perseverate on) is fantastic and consistent. See the art on the cover? The books are packed full of art that level of quality. To the gills. The only criticism is that the bold layout choices make the columns of text writing into a challenging read for me, at least in digital format. The font feels a medium or bold set, even for the body text, and my eyes glaze by the end of a paragraph. Luckily, though, most of Watt’s writing doesn’t range more than a paragraph for a single item. The ones that do are usually the major characters in specific locations, and should they be shorter? They’d be easier to run, but their descriptions are so compelling: “The giant is waking, and crumbling to dust. Oola must learn all she can. She only agonises over her lost memories and the evaporating resources.”. I don’t think we’d be better off without these descriptions, but maybe we could use a lighter weight to make it easier to read in this level of consistent density.

The final seven short zines are specific keyed locations on this hex map. Each of these are very cool, but interestingly aren’t included on the hex map descriptions where all the others are. This makes sense as they’re not included in the main setting book, but it makes them a clumsier addition. They, like the main book, do not share a common structure, and while they’re all good, Alfred Valley and Joel Hine’s really stand out as being compelling and places with a reason to explore rather than simply a vibe. That said, I’ll call out Kienna Shaw’s piece because it’s genuinely a great vibe, even if I don’t see a reason why I as a person would actually attend the ball.

Ok, that was a lot of reading, and it took me a few days. I was definitely right on the money with my first impression that this should all have been a single book. There are just not many rules, and they’re hard to navigate amongst the setting information. It’s very well written, although longer-form than my taste leans, and the guest writers contributions are decent to excellent. But the lack of incorporation of the guest writers works into the setting book is an oversight that weakens that setting book overall, which is otherwise excellent. The entirety of Cloud Empress’s releases so far give me a confused sense of what they’re trying to be: It seems like they want a somewhat pastoral, travelling company type gameplay (with skills like farming and needlework) but haven’t provided the tools to do that. They did a better job than Beecher’s Bibles did (even if Beecher’s Bibles didn’t telegraph that gameplay as well as Cloud Empress did), but not enough for what they communicate. What they’ve written instead, in the hex-crawl and keyed dungeon locations, is a more traditional wilderness fantasy exploration game with a unique setting. And there are world elements that support that well! Crests, Spores, the dangerous combat system — all of this supports some interesting, heavily-themed traditional dungeoncrawling play. The stronger supplementary material supports that kind of play as well, with the other supplementary material somewhat listless; I just wish that the other modules actually were better supported by the rules. What’s the point of giving me new rules, if they don’t support the type of gameplay you’re aiming for?

All in all, I suspect what I’m experiencing is a sense of betrayed expectations: The references, the descriptor of “ecological sci-fi” and the promise to “find a way to thrive, live and love in the psychic wreckage of earth, scavenging” is hinted at by the modifications to the Panic Engine and then gives way to a traditional mode of play, unsupported by the supplementary material and the setting book. Yes, I can still play that game — I could run Cloud Empress in Fifth Edition if I wanted to as well — but I feel like if you make a promise, there should be support for the kind of play you want, in the modules, in the setting book, or in the rules. Somewhere. I wish I was seeing it, but I’m not.

That fairly major complaint set aside, this is well-written, an intensely compelling far-future post-apocalyptic setting, weird and unique and familiar enough to me that I could easily make it my own, with popular enough referents that I could easily sell it to friends to get them to join my table. The Panic Engine is fine here, and although it doesn’t support the play that it promises, it still makes for compelling, high-risk gameplay. What Cloud Empress actually is, it is pretty damned good at. It just isn’t everything it says it is.

(For what it’s worth, today, when I finished reading Cloud Empress, I was going to go to an air-conditioned shopping centre and shop for Christmas presents, but my wife ran late with the car, so I did this instead.)

Idle Cartulary