I Read Games reviews are me reading games when I have nothing better to do, like read a module or write or play a game. I don’t seriously believe that I can judge a game without playing it, usually a lot, so I don’t take these very seriously. But I can talk about its choices and whether or not it gets me excited about bringing it to the table.

I wanted to write some room descriptions for the Mothership module I’m working on, but my kids are being clingy, so instead I’m reading the Alien RPG while they watch Trolls World Tour. This has been on my shelf for three years, and I remember bouncing sharply off it when I first got it despite being excited to play it. I’m going to read it again, and this time take notes.

Alien is the exact large form factor high production value kind of book you’d expect from a big Hollywood IP. The art inside is technically exceptional (I couldn’t criticise any given piece of concept-style art in the book), but on the glossy all-black paper stock it all blurs together. The art misses out on the breadth of flavour of the movie (and it’s sequels) as well, with no scenes of camaraderie or joy, it often feels more inspired by Bladerunner and Dead Space than Alien itself. A friend described it as “Exhaustingly Prometheus and not enough Nostromo” and that hits the nail on the head with regards to the issues with art direction in the book for me.

Font and layout choices are surprisingly large-point and extended, with lots of empty (although black) space and leaving lots of space for the art to represent itself. It’s mainly in two column layout, with huge double page chapter headings. All of these things together give the impression of a smaller format book that has been zoomed out into a larger format. I suspect that in the environment it was released into, Mothership had just came out with cannons blazing and I wonder if some of the large-text, spacious layout choices were made specifically to stand apart from the major rival in the space. I find it surprising that the typographical choices appear to be trying to modernise Alien (or perhaps take their cues more from Prometheus). Even the title card isn’t quite the classic Helvetica Black of the original movie, if I don’t miss my mark. It’s an interesting choice to choose typography that isn’t reflective of the movie itself — there’s no Pump Demi to be seen — but rather the 40 years of science fiction the were inspired by it in turn.

For me, the combination of simplistic, unimaginative typography, gloomy art and layout, and black gloss pages, make reading the book a bit of a drag. It’s a layout that would shine in a zine, but loses its sheen in 390-odd page hardcover.

I’m not surprised it’s heavily overwritten, but it just seems like a huge miss that so much time and space is spent explaining things that are self-evident to the kind of people who would buy this book, like the careers likely on the frontier section. As someone who isn’t a huge Alien nerd, there are other decisions that scream trying too hard to appeal to casual fans, like the rendering of MU/TH/UR as Mother. The weird contrast, though, especially in the first 25 or so pages, is that it’s also overspaced — I’m certain the entire introductory chapter could take half the space, and Mothership 1e doesn’t even bother with an equivalent section because nobody is buying this book who doesn’t have a grasp on the Alien universe.

This overspacing, extended font choices and overwriting results in a usability problem throughout the book. Things that should and could be summarised in a spread are done in five. The relatively simple character creation could be a pleasure, but is instead a chore. I have to read 20 pages of class descriptions for 9 classes. For the typographically literate out there, we’re talking eight words wide columns at times; just terrible use of space. My hands are sore from turning pages so quickly because there’s so few words on each one.

The system itself is a simple dice pool system, with the addition of stress to simulate panicking (they’ll explain that in 45 pages time); you can bet stress to reroll, which is a neat risk-reward mechanism that fits well into the Alien worldview. It’s a mixed traditional and story game approach (it even has Story Points) which…well, maybe it’s just my predilections, but it’s like it doesn’t know what to be. I think a pure story approach would work pretty well for this kind of horror — I could especially get excited about a Forged in the Dark game based on Aliens — but this game seems afraid to stray from a more traditional conflict resolution framework.

I won’t go into detail about the way talents interact with skills, but suffice to say it’s neat, and maximises the tactical complexity of the system, while being a little too fiddly. I suspect you’ll forget when you’re supposed to use them. It should be said that most equipment and vehicles are fully illustrated, which is both impressive and contributes frustratingly to the poor usability of the text, for the same reasons as I’ve now stated at least twice.

I’m at half way through, and I’m exhausted. The layout and green on black text is just tiring for me to read. Everything here that’s said with paragraphs could be said with mechanics or more succinct worldbuilding methods like tables. I can’t bring myself to drag my tortured eyes over another page. I’ll skim through so I don’t miss anything major though.

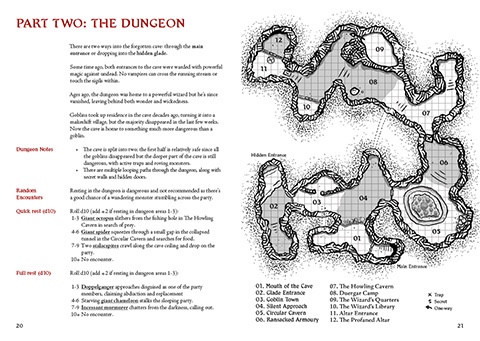

Ok, there’s one other thing that stands out in the second half of the book: The final sections on campaign play and the starter adventure are both just solid good stuff. Campaign play is filled with simple Traveller-inspired generators, NPCs and locations. The adventure is full of interesting characters and appropriately keyed locations. The best stuff here effectively in an appendix.

Alien: The RPG isn’t the RPG as soft fiction reading, it’s the RPG as an art book. But the layout isn’t striking enough (fair, too, at 390 pages) and the art isn’t good enough to justify the direction, especially not with things like Ultraviolet Grasslands out there being great attempts at art-heavy RPG while still making things striking and useable. This game, if I spent some time making a decent cheat sheet, would be perfectly playable. It might, maybe, be better than Mothership. But the book itself is barely usable for me, for a huge variety of reasons, and why would I choose a difficult to use book, when it’s main competition is, while not in my opinion for beginners, at least as good, easy to use, has a massive amount of content and a hugely active community.

I can’t think of a reason, to be honest.

20th August, 2023

Idle Cartulary