Bathtub Reviews are an excuse for me to read modules a little more closely. I’m doing them to critique well-regarded modules from the perspective of my own table and to learn for my own module design. They’re stream of consciousness and unedited harsh critiques. I’m writing them on my phone in the bath.

Barkeep on the Borderlands is a fully illustrated 59 page module by W.F. Smith known as Prismatic Wasteland, with a broad range of guest writers. I backed Barkeep on Kickstarter and am reading a digital version, and I’m both in one of the communities thanked in the book, but also friends with a few of the writers. It’s system neutral, but unashamedly styles itself as a “pubcrawl”, a style of play with its own rules distinct from hexcrawls, dungeon crawls and point crawls. It is set in the distant, cosmopolitan future of classic module B2: Keep on the Borderlands. The antidote to the monarch’s poison has been lost amongst the Raves of Chaos festival, and a great reward awaits those who find it. Meanwhile six factions vie for power in the Keep as the prime ministerial election is decided.

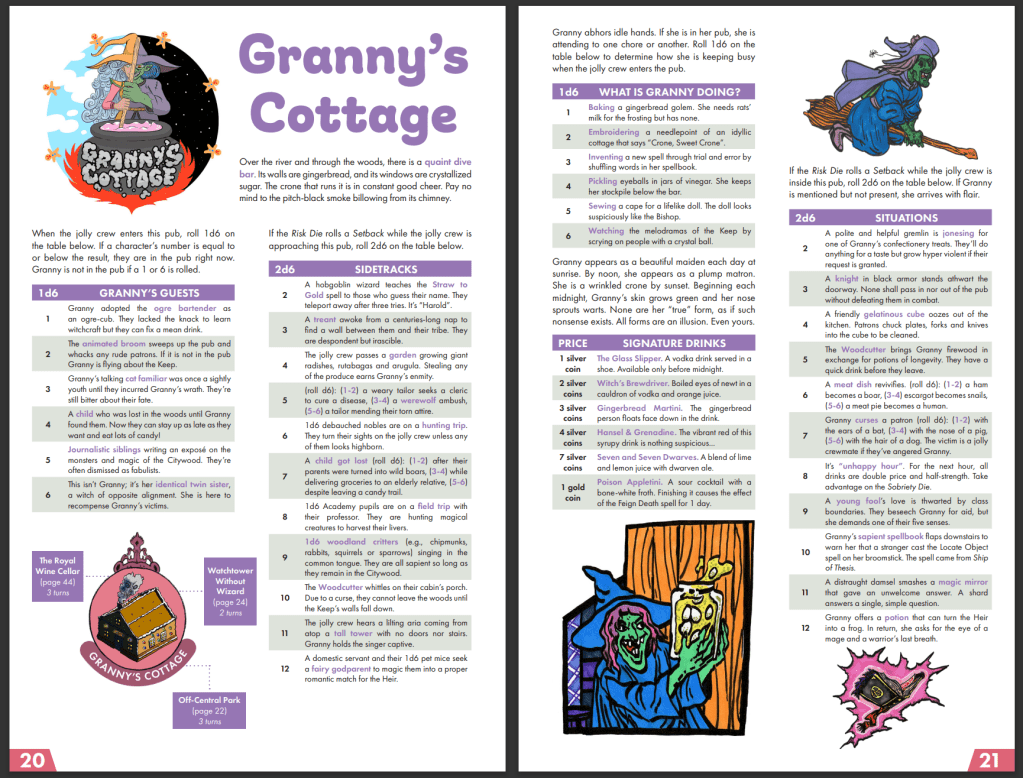

W.F. Smith’s writing style is lighthearted and holds together a module that could easily veer into ridiculousness in the derogative, but doesn’t. Most of the writing is in bite-sized tabulated format, is evocative enough to springboard off the other writing in the module, and also relies on the GM to fill in gaps which is exactly the way I like it. The humour sneaks up on you in each entry, as well, but it should be clear that I expect Barkeep played as intended (as a pubcrawl) to result in a ridiculous and gonzo campaign, as most elfgames trend towards comedy even in the absence of a comedy setting. I appreciate especially how the tables are used to tell stories for the GM, often being an art form: “(1-2) a weary tailor seeks a cleric to cure a disease, (3-4) a werewolf ambush, (5-6) a tailor mending their torn attire.” This kind of writing is elegant and occurs throughout the product. It feels like W.F. Smith edited all the other authors for consistency, because it’s a shockingly consistent module for one with so many writers.

Structurally, we have 20 pages of set up and rules, and the remainder is pubs. The first section feels a little too much as you read it looking forward to the money of the module, but honestly if I look at the individual sections I can’t fault them too much individually. The adventure is a complex one: It involves time passing and things changing, election politics, and theft investigations, and so these sections are necessary to keep the ball rolling as anything other than a book of pubs. Unfortunately, if you want to run this as a GM, the 20 pages of set up is necessary work, in the same way that the first section of Witchburner was a bit much for me, but worth it for the outcome.

The layout is flashy and straightforward, with clear headings and use of colour for clear delineations. I wouldn’t recommend reading this on your phone, like I tried to do. It’s designed to thoroughly take advantage of the print format. Different pubs have unique colour signatures and title fonts, and fit to a spread. I’m usually an objector to having such highly variable headings, but they work here due to a very consistent format with exemplifying art, summarising paragraph and top left placement. Art is almost always palette-matched to the colour scheme of the associated pub, and uniformly matches the aesthetics of the piece. Every pub has its own stylised mini-map as well. I should probably back track a little and say that while the majority of the text is exceptionally laid out, the introductory sections don’t benefit from the consistency of the pub structure and are a little messier and more ad hoc.

Writing more about Barkeep is challenging, because it’s a complex and intentionally varied experience, so I might pick out a few favourite moments of mine in it, by way of illustration. I love the way the politics are not subtle, but not communicated to the players through exposition: “Lizardfolk nuns hand out red pins. “Remember the Iron Fens Uprising. Mourn, yet organize!” Dwarf revelers try to get them arrested by Chaos paladins.” I enjoy how the signature drinks of each pub are simply excuses for the writers to be a little flashy and make puns: “Newest Corpse Revival. Won’t actually animate you with grotesque unlife but feels like it could. Gin, bits of orange.” I love how each situation (of which there are at least eleven for each pub) feels like a potential set up for an entire night of gamming: “A thrown spear narrowly misses the Barkeep. The bar is closed until somebody faces their wrath”, as do the sidetracks that are intended to be tangents: “A couple’s date is interrupted when one transforms into a wolf. Their date cries for help but won’t allow the wolf to be hurt.” Most of all I enjoy the subtlety of the connections: “The owner wanted to sell this rooftop karaoke bar and retire to a tropical island but discovered an endangered bird roosting in the rafters. Now any sale is prohibited by royal decree.” and then, in a table: “The phoenix in the rafters mistakes an ashtray for its murdered hatchling. The bartender commands everyone to sing a lullaby to soothe the phoenix’s fiery anger.” These are common, and excellent examples of how to world build without lore and endless exposition. To be clear about these examples, normally I take thorough notes as I read the module to find good exemplars of the writing. For Barkeep, I just flicked to a random page and had to choose from multiple excellent set ups on that page, all of which were worth quoting. This book is dense with gameable concepts and explosive situations in a setting that gives strong reasons for the Jolly Crew to participate in both debauchery and investigation, as well as strong reasons for the situations to be explosive.

Barkeep is a unique experiment in a specific type of module, and I think it succeeds for the most part. It’s intended as a social adventure, which is exactly my jam (if I wanted a combat-packed session, I’d play something with tactical combat rules), but it doesn’t try to be an exploration-based game in the slightest. I imagine playing this roughly in real time, with the Jolly Crew (as the party of PCs is called) cramming as much debauchery and investigation into each night of partying as they can. The effort in running and setting up I think would reward the right group of players, but it’s an irreverent pitch that wouldn’t be for everyone. If I recall correctly, my recommendation for Witchburner is that it’s close to perfect a social intrigue game, but the dark and hopeless premise may not be fit for your group. If that darkness and hopelessness was what prevented you running Witchburner, Barkeep on the Borderlands is your light-hearted and irreverent solution. I personally prefer the darkness and twistiness of Witchburner, but Barkeep is probably a better social module, and it’s definitely going to be funnier.

17th July, 2023

Idle Cartulary