A lot of people ask questions like “should I write a module as system-agnostic, or for a popular system?” or “if I write a module for an unpopular system like X, will nobody read my module?”. I’m about as deep in the module game as you can be, so I thought I’d talk about what it means to be a system agnostic module (or system neutral module — I’ll use them interchangeably) and try to answer these questions.

To be system agnostic? Or not to be?

In most modules, you are likely to engage in the types of actions that a specific genre calls for. Games have mechanics that tie into those actions: in Liminal Horror, advancing doom; in Mothership, panic and stress; in fantasy and most other roleplaying game genres, violence. In old school roleplaying there are actions which often don’t have rules — sociopolitical play, intrigue, or solving a riddle for example. Players are expected to play those aspects of the scenarios out sans rules. Whether you’re choosing system agnosticism for your module or not depends on whether you’re writing a module where you’re anticipating actions typical of the genre it’s in. Players do not read the module: The fact that I don’t write in 5th edition stat blocks does not mean my 5th edition players aren’t going to treat my monsters as 5th edition monsters. If you write something system agnostically, you’re just creating work for the referee unless the genre expectations are right there on the label.

That said, I’m going to break system agnostic modules down into 4 categories, dependent on why and how they’re system agnostic. When you’re looking at these, consider what your module fits into, and why it has ended up there.

Category 1: Freeform Modules

Some modules are system agnostic largely because they are almost entirely contingent on social interaction and investigation. You don’t need any rules to play them. You just go around talking to people, taking notes and making decisions. There isn’t any reason in the modules themselves for the types of actions that most games have rules for. Examples of this are Barkeep on the Borderlands and Trouble in Paradisa. These kind of modules need a familiar framework: Trouble in Paradisa relies on the players knowing how a soapy murder mystery works. Barkeep, a less familiar concept, suggests you play it using Errant or Cairn, despite not containing any other reference to those games, relying on those frameworks to support the content of the module.

Modules in Category 1 are often unintentionally in this category: The situation being presented simply never needed to have a system attached to it, and often modules that could be in this category aren’t simply because they started their life as a module for a specific system, or because naming them that way is simpler than having suggestions like Barkeep on the Borderlands does — Witchburner and Owe My Soul to the Company Store are examples of this.

Category 2: Experimental Modules

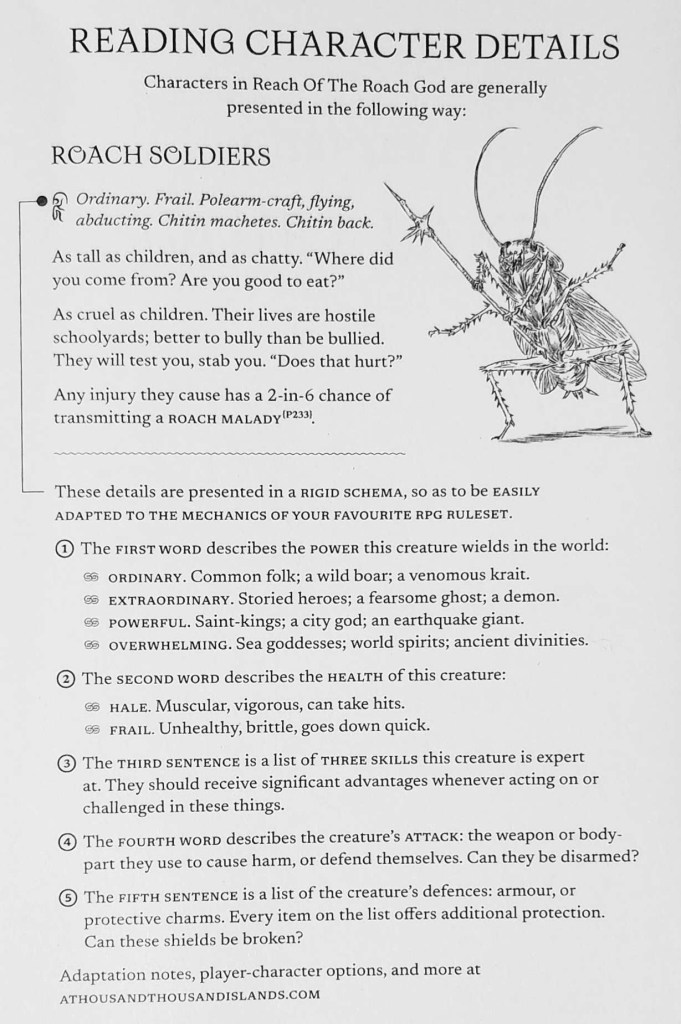

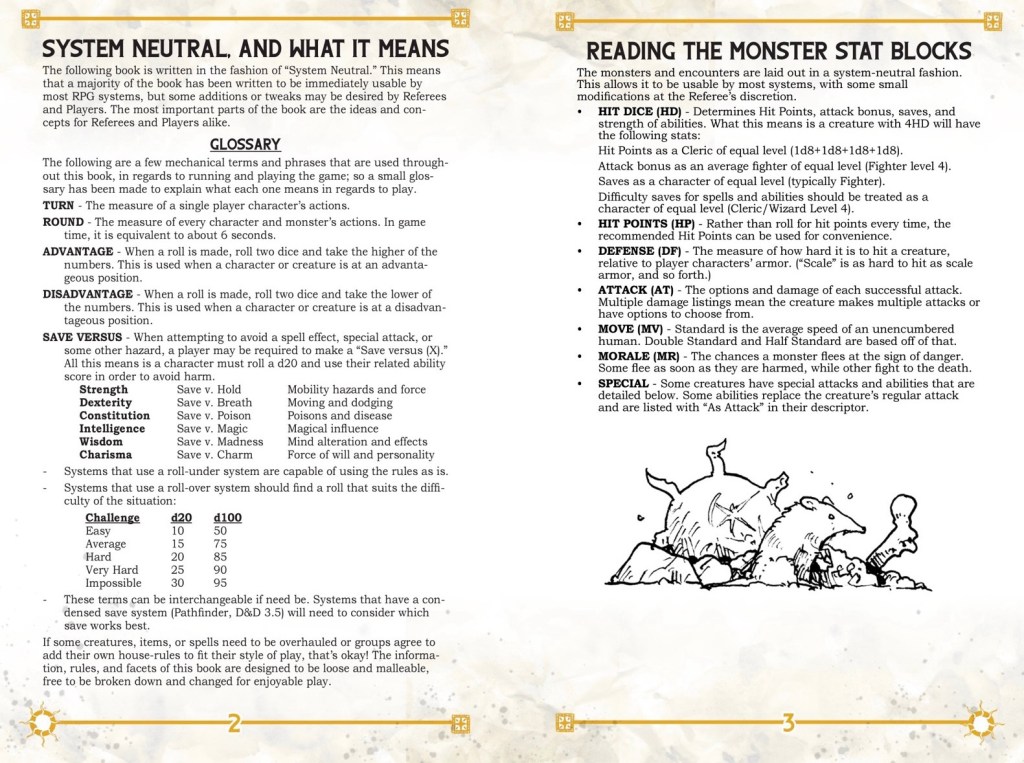

Some modules are intentionally avoiding using mechanics and numbers, at least visibly, in their text. This might be aesthetic, or it could be for the sake of being avant-garde. Typically, these are written with a deep consideration of all of the systems in the hobby. I did this with my Ludicrous Compendium, which is an English-language haiku bestiary, and in the upcoming Bridewell, my Curse-of-Strahd but in verse module. But it’s best exemplified by Reach of the Roach God:

The 5 sentences here, map directly to items in most common fantasy stat-blocks, and are easily translatable, but they’re also thoughtful: They’re written this way to distance themselves from the cultural implications of phrases like “AC as chainmail”. If you write these kind of descriptions without a deep consideration of what other fantasy systems need, you’re simply leaving work for the referee to do; they need to be both lyrical and able to be readily interpreted for play.

Modules taking this approach must be super intentional about their choices: They want a broad audience through a very specific non-mechanical lens. It’s challenging to do well and requires some experience playing the games your module is likely to be translated to.

Category 3: System Stealthy Modules

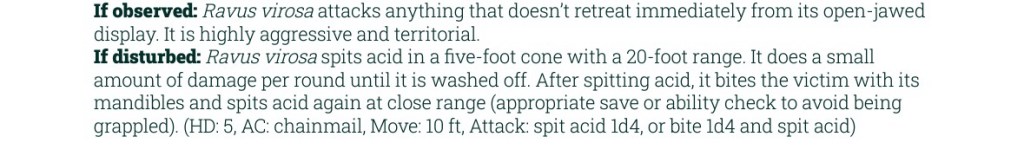

Most system agnostic modules are category 3: half of a stat block for something that’s familiar with a lot of people, usually B/X. When I casually say “No module is system agnostic”, which I from time to time do say, I’m referring to this category. An interesting example of this is Mouth Brood:

In Mouth Brood, you play modern-day scientists venturing into an alien habitat filled with of strange organisms. Nobody wears chainmail in a modern day science expedition. The “chainmail” of Ravus virosa just indicates how dangerous and sturdy the organism is relative to the player characters, in a common language. Mouth Brood and other Category 3 modules aren’t actually written for (for example) Old School Essentials, despite being directly translatable — it leaves out a lot and relies on referee familiarity with the commonly understood texts.

These modules are usually system agnostic through the specific intention of adopting a lingua franca. Authors who adopt a Category 3 approach want as many people to understand their module as possible. I personally think this is actually the best approach, assuming you’re not making a socio-political module — it’s very succinct, and leverages the knowledge of your readers in an efficient way that acknowledges their intelligence and familiarity with the hobby.

Category 4: Indifferent Modules

These modules aren’t system agnostic, but they are part of a venerable lineage that’s really “I wrote this for my own home game and it’s homebrew rules”, and rely on most of the same principles as Category 3: The familiarity and intelligence of the referee to interpret the text. Great examples are the first edition of Ultraviolet Grasslands, which is as written up for a system that wasn’t to be released for another 5 years, and You’ve Got A Job On The Garbage Barge and Neverland, both written for their authors homebrews of 5th edition. You could also include modules like Into the Cess & Citadel and Ave Nox in this category, as well as modules like the Dark of Hot Springs Island which assume you’ve got the statistics for all of the creatures for the game of your choice.

These Category 4 modules are most likely system agnostic through indifference: This is the system we played it in, here is our stats, we don’t consider putting the effort into converting them worthwhile. I honestly respect this: This goes back to the roots of the hobby, where duelling imaginary versions of D&D coexisted in the pages of Dungeon Magazine. Like category 3, it acknowledges the intelligence and familiarity with the hobby that the reader has.

Who cares about these categories?

Nobody, not even me. I don’t really consider category 4 modules meaningfully different than category 3 modules; if I ever use this categorisation I’ll probably say things like “this is a Category 3/4 module”, but I can’t imagine anyone will use these categories in this way. The purpose of going through these is to exemplify: There’s a range of ways to make your module system agnostic, some very intentionally, and some unintentionally. It’s a way of supporting you to answer the question of why you’re considering making a module system agnostic.

People will play anything, however wild.

Your first consideration should be whether your module is interesting or fun enough for people to want to play. People will play your module however wild the format. This entire post is moot, if you have something compelling.

Should I write a module system-agnostic, or for a popular system?

We return to the questions at the top of the post. Consider these two questions:

What did you playtest it in? Easiest to write it in that system. If that system is a homebrew system, it doesn’t matter. Good modules get played even when they’re for systems that don’t exist.

Can your concepts be briefly described in Stealth B/X terms? If so, that’s a lingua franca, use that, if you speak it as well. Good modules get played even though phrases like “armour as chainmail” are silly when applied to science expeditions.

Would my system agnostic module be better if it were written for a specific game? You could reframe this question as “Are the players of my system agnostic module likely to engage in the types of actions supported by a specific game?” In this post I’ve listed many modules and I think I might have a different answer for each, but a good module is a good module, irregardless of whether or not it is system agnostic, just as a good book is a good book, whether you read it or it is read to you.

If you’re answering these three questions with “no”, you might be writing a socio-political module or an object of undeniable beauty that would be regarded as art by anyone off the street. In these cases, do what you want. System agnostic is a great choice for you. You might also not know any games well enough to understand how to use their rules. If that’s the case, your research for this module is to learn to play those games. Even if you choose to go for system agnostic your familiarity with the games that people will be playing it in will help your module for better.

The insidiousness of marketing

I’m not a marketing expert, but some people might feel that writing your module for a popular system may make it more likely that your module is popular. I’ve released system agnostic and Cairn editions of Hiss, and they have almost identical numbers, so I’m not convinced this is true, but I understand how it might look that way. There’s undeniably an audience out there looking for Mothership modules and Liminal Horror modules etc. If you’re writing contemporary horror, you’ll probably get more eyeballs by participating in this years Liminal Horror jam than if you publish it system agnostically. But to be contrary, this post has listed a lot of modules that released system agnostic (Trouble in Paradisa, Witchburner, Reach of the Roach God, Mouth Brood, Neverland, Ave Nox, Ultraviolet Grassland 1st Edition, Vampire Cruise and Crush Depth Apparition) that nevertheless found popularity. While the fear that you’ve wasted your time writing something no one will read is very real, marketing is something to worry about after you have written your module, not before. If that’s compelling, people will come.

Should I write my module system agnostic?

If it’s an essential aspect of the identity of your module, definitely. Otherwise, do it if you want to. The important thing is that you make the module. The take home message here is not that it doesn’t matter whether your module is system agnostic or not, but rather that you must not talk yourself out of writing the module before you even finish, simply because you’re not sure which game suits it best. Don’t wait to create. Just do it, then answer these questions to decide whether you want to go system agnostic or not.

Idle Cartulary

Addendum: Symbolic City responds, arguing that choosing a game is standing in solidarity with the creators of that game, and particularly independent games need endorsement.

Playful Void is a production of Idle Cartulary. If you liked this article, please consider liking, sharing, and subscribing to the Idle Digest Newsletter. If you want to support Idle Cartulary continuing to provide Bathtub Reviews, I Read Reviews, and Dungeon Regular, please consider a one-off donation or becoming a regular supporter of Idle Cartulary on Ko-fi.

Leave a reply to Idle Cartulary Awards for Excellence in Elfgames – Playful Void Cancel reply