Each holiday season, I review different modules, games or supplements as a thank you to the wider tabletop roleplaying game community. All of the work I review during Critique Navidad is either given to me by fans of the work or the authors themselves. This holiday season, I hope I can bring attention to a broader range of tabletop roleplaying game work than I usually would be able to, and find things that are new and exciting!

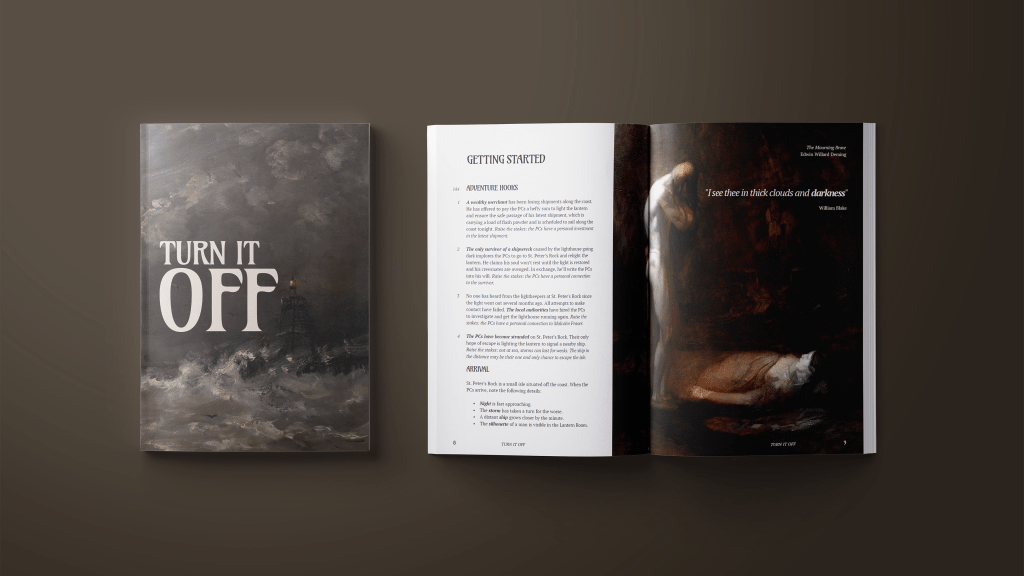

Turn It Off is an 8 page module for Knave 2e by Sean Audet. In it you explore a lighthouse in an effort to extinguish its’ light and hence prevent an ancient eldritch abomination from rising from the dead.

The module opens with the key, horizontally split across a spread, with an exterior of the lighthouse at the top, and the map of the lighthouse at the bottom. The choice of a lighthouse means that descriptions of all the rooms and the exterior are entirely on the map, with page references for more details. Excellent stuff, and although it would be a little better had this been the inside front cover with regards to readability in print, the map is small enough you can probably hold relevant spaces in memory.

Then we have 4 adventure hooks; these are excellent damned hooks. Each one has a juicy worm, and as icing on that cake (mixing metaphors, sorry), they also have a potential way to raise the stakes in addition to that juicy worm. These are what hooks are supposed to look like. Next up we have the 3 characters occupying the lighthouse – these also slap, and are nice and brief and easy to run from. Then, we have our events and encounters, which progress the worsening of the storm and the nearness of the approaching ship, while also handling the random encounter table. The only thing I don’t like about this little system is that you move to Table B “when it feels right to increase the tension”, which I don’t love as a criteria in an OSR style game.

Then, all of the locations are expanded into a half page column. While these are a little excessive in length in my opinion — there’s not a lot of weird and wonderful things going on in these rooms — it works well, because we have the summaries to go from on the map. We’re only going here for details, and I for one don’t know what I’d find in an 18th century lighthouse, so it’s appreciated. The thing missing here is that the characters are listed earlier — the choice makes sense, but means a bit more flicking to and fro.

What’s nice about Turn It Off is the difficult decisions you’re forced to make. You’re wondering the lighthouse looking to repair and light the lantern, ever the while looking out the window at the approaching ship. If you don’t light the lantern, all aboard the ship will die. However, as you explore the lighthouse, you’ll find clues that lighting the lantern might cause a greater evil to come to pass. It’s a trolley problem, and that’s precisely the kind of problem I love to see in small modules like this one. Thankfully, it gives some options for a more heroic finale if your players aren’t into the doomed resolutions that are the player’s options out of the box.

I think the biggest problem a lot of people will have with Turn It Off is that it, like Late Stage Death Cultism that I reviewed yesterday, is fairly linear. You can’t really avoid it with an environment like a lighthouse, to be honest. It also opens in specific circumstances: It’s night-time, it’s a storm, there’s a distant ship, and you can see a man silhouetted against the lantern. All of this works really well for the specific vibe that Turn It Off is going for, but it requires a table that is signed on for a moody, locked-in creeping horror vibe, rather than an inventive, problem-solving OSR romp. In fact, when I reviewed Late Stage Death Cultism, I suggested that using its’ model to work on an alternative time period, which is precisely what Turn It Off is doing. I feel like Turn It Off would only be better were it to have Troika! backgrounds rather than hooks, or pre-gen characters.

Turn It Off uses the Explorer’s Template for it’s layout, but it does so with flare, breaking the grid, combining spreads for impact, and using horizontal splits. It’s really good. Art is in the public domain and is excellently curated, and all attributions are on the page. The large, gloomy choices of paintings are offset by poetry quotes, that add a lot to the aesthetic as well. All around smart choices, for a low-budget module.

Ok, so overall, I think Turn It Off slaps. This is precisely what I’m looking for in a one-shot. I do think it might do better with pre-generated characters, particularly given the hopeless outcomes associated with the devil’s bargains your characters are forced to make. If you’re looking for a one-shot and your table is one that takes delight in hard decision making, then I wouldn’t hesitate to pick Turn It Off up.

Idle Cartulary

Playful Void is a production of Idle Cartulary. If you liked this article, please consider liking, sharing, and subscribing to the Idle Digest Newsletter. If you want to support Idle Cartulary continuing to provide Bathtub Reviews, I Read Reviews, and Dungeon Regular, please consider a one-off donation or becoming a regular supporter of Idle Cartulary on Ko-fi.