I Read Games reviews are me reading games when I have nothing better to do, like read a module or write or play a game. I don’t seriously believe that I can judge a game without playing it, usually a lot, so I don’t take these very seriously. But I can talk about its choices and whether or not it gets me excited about bringing it to the table.

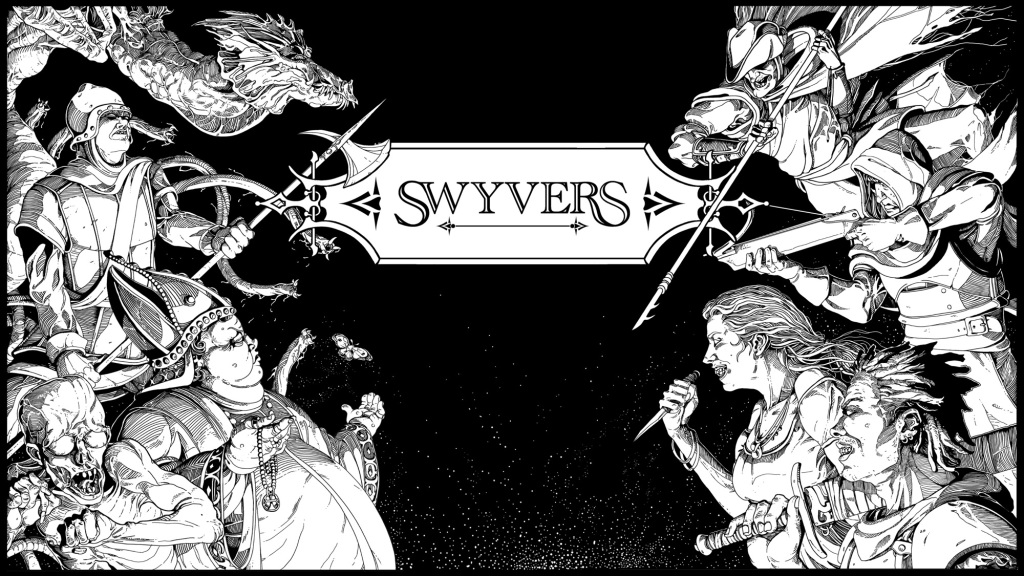

Today is all prep for my daughter’s birthday party, but I need a break, so between blowing up balloons and assembling cakes, I’m reading Swyvers. Because of the nature of my day, this may be a more chaotic read than usual. Swyvers is a 95 page rules light roleplaying game by Luke Gearing in which you play criminals in a corrupt, steampunk city. Obviously, this invites direct comparison to another game in which you play criminals in a corrupt, steampunk city: Blades in the Dark. I’m not going to bother avoiding those comparisons, and actually I’ll lean into it, as I love a good campaign of Blades in the Dark, and I’ve previously complained about Spire being not enough like Blades.

One thing that sets Swyvers apart straight away is the approach: The book is described in the intro as being “light-weight set of rules married to a full set of tools and tables”, which makes me expect this to be (given the modus operandi of the author) something of the minimalist elf game variety, perhaps verging on Braunstein, attached to a randomised setting guide. This leaves me a little nervous: Luke Gearing is an exceptional writer, but I’ve written before about my objections to Brian Yaksha’s — also an excellent author — approach to setting and how this hard anticanon approach can make settings unapproachable to me. There’s a place for concrete setting and a place for random generation, and it’s a rare book that walks the tightrope successfully in my mind.

Character creation for Swyvers is an elegant 2 pages, with most of those being a list of trinkets reminiscent of Mothership’s patches. These are for the most part, though, humorous and feel leveraged at use in play rather than as a sideways glance at character building. After a little more world building in the form of “atypical PCs”, we launch into the equipment section, which is mainly — no joke — prosthetics. The brevity of the character creation and the emphasis on both gameable equipment and disability to me speaks clearly to what Swyvers is intended to be: A violent game of nasty desperate people, likely to die or be injured for stupid reasons at stupid ends.

The rules though, whilst hardly being crunchy, are a solid 40 pages, covering skills and saves, fighting, gaming and disease, morale, timekeeping, advancement, encumbrance downtime, and fences: Nothing exciting, and pretty basic stuff.

This is a very save forward system, but it does involve skill rolls as well, rather than the more extreme save only systems. Combat is intentionally chaotic and weird, and is a little clumsier in response to that — I’d need a wee referee’s screen during combat, I think. But the consequence of combat here is both humorous again — hence the prominence of prosthetics in the equipment section — and the reason for the skills section at all. We’re leaning into this silliness of the 5th edition check here, I think, evidenced by the skill check instructions: Actions requiring training that players do not have; Actions which rely on information the Swyvers have access to; Actions relying on the Swyvers physique or ability alone.

The investment and property rules lm interesting and evocative. I’m not sure they’re easily useable — we have no framework or procedures in this game, so no formal downtime — but I could see a player flipping through this and realising they were desperate for a smut library or a printing press. These aren’t very mechanical — the most you get is 5% chance of something per month — and I wish they had a little more heft, because making something that generates significant narrative effect seems unlikely for the work put in. I’d be inclined because of the OSR-iness of this game, to play in real time (there’s no guidance for this at all), which means my 5% chance per month is only 60% chance in a year of play. I’d like my players investments to result in more concrete narrative consequences than that. That said, the lack of mechanics here suggest it’s really more intended to direct narrative “diagetically” in the sense that this is not a game about mechanical heft at any point: most weapons don’t even have mechanics attached to them (the most mechanical been “d10, 3 round reload, ignore Armour”). The idea of my entire campaign pivoting to criminal Bridgerton after the purchase of a printing press, really tensions in my mind at the fact that that printing press doesn’t provide you with any suggested perks at all. This can’t really relies on a particular type of table, and given the importance of the lists to the world building, probably one that flips through the book themselves to recognise these opportunities.

There is downtime, called expenditure: A way to use the money you steal. There’s no long term goal line in Blades in the dark; it feels like the swyvers aren’t meant to survive long. Expenditure feels like an addendum, but a meaningful one: You get XP by carousing and exposing yourself to drama and plot hooks, you can research for low risk XP, and you can train a “putterer” — basically a sidekick that acts as a backup PC for you if you die, and an assistant in the case that you don’t. As the primary source of expenses, it feels like it’s just not enough, compared to the fact that there’s never enough clinic to go around in Blades in the Dark.

40 pages and we’re into Running Swyvers, explicitly the important part of the book in the author’s esteem; How to run the Smoke, the big city at the games’ core. The problem I anticipated is very much the case here, in my opinion: There is no the Smoke here, just a generator for the Smoke. I don’t think the heist-directed gameplay of Swyvers benefits from me creating parts of the city on the fly: Blades in the Dark feels most heisty when you e paid extra for the fancy maps or on the now defunct One More Multiverse, than when you’re making it up on the fly. So I’m faced with a choice as a Swyvers referee: Do I use these tables to spend hours doing prep, so I can answer freely my players planning questions? Or do I wing it, and my players are just finding out what the city is as it comes? Someone somewhere said that they feel like, if the players are supposed to be experts in the city, Doskvol doesn’t work, because there’s a bunch of lore that they don’t know. It steals their opportunity for expertise from them. They used this as an argument that the city should be entirely (or at least partially) improvised by the players as hoc, because they’re the experts. I feel this argument is a little disingenuous, to be honest, although I know people who experience games this way, because if there’s no existing facts about the city, how can you be an expert in it? And that’s not perfect phrasing, but at least: If you’re supposed to be making plans, the experience of making plans around improvised facts is very different than the experience of making plans around pre-existing facts. This is the argument that perpetually surrounds Brindlewood Bay. I don’t think Swyvers wants to be the Brindlewood Bay of the OSR, though.

I think Luke Gearing’s wants the referee to be inventing the world on the fly, and presenting this to the players. My evidence for that is that in his Pariah session recaps, Luke talks about how he generates each session on the fly, similar to how these tables work. The difference though, is that Pariah is about wandering; Swyvers is about taking information and applying it to steal power, information or money, and dealing with the consequences. You want to be able to make heist plans: There’s no facility for flashbacks here. And the way the Smoke is set up, I don’t think it actually support that style of play. The random encounters just aren’t gameable, aside from the very specific list of criminal opportunities. This Smoke is mainly things I’d rather have been told the answers to, and not enough to help me run a session. Could I build my own Smoke, using the tables here? In combination with the implied factions here and in the bestiary, I probably could, yes. So could basically anyone willing to pick up this book. Would it be easier to just run a campaign in Doskvol? Yes, and I’d prefer to. I’ll come back to this, I’m sure. But back to the book.

The bestiary is mainly beasts: A bit of a disappointment to be honest, given this game isn’t really a dungeon crawler — or at least this far hasn’t presented as one. I like the weird and unique monsters, but monsters don’t feel like they’re truly a part of this world in the same way they are in more traditional fantasy. I’d like to have seen more actual characters from the Smoke, and more actual gangs or factions. I value that content. Gearing has a knack for creatures that feel fun to incorporate, though. It’s good stuff.

There’s an interesting magic system. It seems cool. Very culty, it reminds me of the videogame cultist simulator in a positive way. You don’t learn about spells until you find a spellbook — this is supposed to be rare and illegal, although there’s one in the starter adventure. As you learn more of magic, you can (spoilers if you’ll be a player) substitute components for cards, add specific effects, and make bargains with devils for permanently held face cards, in exchange for service. These systems are really, really neat, and like the best of the systems in Swyvers, are likely to drive play through player agency. I like that it feels alien to the rest of the systems in the game, due to the black jack cards system, as well. You’re more likely to chicken out on completing the spell, and being aggressive will likely cause certain doom. I like that the magic system is difficult, and likely to be goal oriented and drive play. But also, such a big section makes it feel like it’s expected to be core to play in a way that’s out of step with the way it’s presented in-world. At least, it’s packed full of Gearing’s signature vibrant and evocative writing, though. It’s stellar stuff.

The shortcomings of Swyvers are hammered home by the interesting and very good module that comes at the end: There’s only one. I can’t adapt just any module to Swyvers easily: We’re not heroes but criminals. It doesn’t matter that Blue Cheese, Left to Rot is a very good starter module (it is, genuinely, pretty great, Gearing doing a Gus L impersonation after watching too much Peaky Blinders), because this game requires more modules, and will need significant support from either Luke Gearing or Melisonian Arts for there to be enough to get things rolling. It thrives with a well-written module. I’d run a Swyvers one-shot using this module with pleasure. But the amount of work that I’d have to put into the second session (or likely group of sessions) feels prohibitive to me.

Based on this, what does this Swyvers campaign with no real city actually entail in play? I can only imagine this: The referee starts with the built in starter, then at the end of the heist, the players decide their next heist, and the referee designs the dungeon for them for next few sessions. The referee improvises using the tables provided enough for any free play that might occur in the gaps between dungeons. This feels like a hellish loop for me — I don’t think the tables here provide me with sufficient meat to improvise a city and have it feel as complex as a London or New York analogue should be to be entirely honest — but it may not feel hellish for you.

I don’t like the layout. Gearing is on the record as not considering layout and infusion design a key part of game design (or rather, that the writing is far more important), and it shows here. Good luck quickly finding the “research rules”, or figuring out war magic is available in a pinch. Subheadings are subtle and plenty of things aren’t flagposted well. We’re in two-column layout, which works just fine, but the information design is just not very strong in Swyvers at all. Things are just in whatever order they were written, it appears, rather than by type (to my eye) or even alphabetical. To play Swyvers would be to write an extended cheat sheet to summarise the rules, something I haven’t done since I played Pathfinder 2e. The rules and writing deserve better. Even the art m, which feels sparing and striking, is uncharacteristically clean and polished compared to the world it portrays.

In general, to me Swyvers’ humour is its main strength. By comparison to Duskvol, a city with very similar fantasy Victorian London vibes, it’s more intentionally comedic, it takes its grimness with a shot of humour. A lot of terminology feels co-opted from dictionaries of slang such as this one. If you’re not already a fan of such terminology, expect to do a lot of googling. But, the vibes it brings are funny, evocative and engaging. It’s full of asides: Every piece of equipment gets a comment that’s purely for laughs: Glass Eye 5s Could lob it at someone in a pinch?This is, to me, Luke Gearing’s most engaging writing in some time, after he’s spent a lot of time on more heady ideas.

But despite its similarities, Swyvers is not Blades in the Dark. It is a dungeon crawler, that wants to lean into the “dungeon as heist” perspective, but without significant support, becomes just another DIY elfgame whose interesting setting is prohibitive of using most of the modules that already exist. If you want to build your own setting, and not use modules, and you’re interested in an off-kilter Victorian crime grot vibe, Swyvers is not just very good, but probably the only thing out there. You could combine this with something like Skerples Magic Industrial Revolution or Into the Cess and Citadel — or to be honest, Doskvol — to fill in the gaps, as generating the Smoke feels incomplete here. You can make this work, if you have the time. It might be with it.

Swyvers in many ways feels like it encapsulates a number of trends in the DIY elfgame space that I haven’t been vibing lately. An over-reliance on random tables as a substitute for actually building a world, and the perhaps related a reluctance to build a world as a response or reaction to the encyclopaedic lore bibles of yore. The insistence on building a games built on the same core engines without consideration of why those engines thrive, namely in my opinion, the existence of 50 years of modules that facilitate play. I adore the counter examples to these trends: Pariah is one, which Gearing has played! As is Gearing’s own Wolves Upon the Coast! And it’s possible to support a bespoke DIY elfgame with bespoke modules, I’m just not seeing enough of this support to justify making the switch. I wonder how much of this is really a core problem with the commodification of the hobby: People producing high quality, expensive, high art modules aren’t going to produce them for Swyvers or your bespoke samurai or age of sail elfgame. They’ll make it for Old School Essentials, or for something else with a sales ecosystem: Mausritter or Mothership or DCC or the like. Why wouldn’t they? It won’t get seen without the art and expense, and they won’t make their money back without customers. We need a drive for simple, low-production quality modules to support games like Swyvers, or there’s no point in producing them.

Swyvers is really engaging, but falls short for me despite its flair for the verbose and evocative. I want a more concrete the Smoke to run heists in, and in the absence of that, I need a catalogue of modules. If there’s a follow-up release: An omnibus of Swyvers heists, I’d revisit Swyvers as a really interesting option for regular play. But until there is one, Swyvers is written off for me, as falling solidly in the too hard to prep and run basket.

Idle Cartulary

Playful Void is a production of Idle Cartulary. If you liked this article, please consider liking, sharing, and subscribing to the Idle Digest Newsletter. If you want to support Idle Cartulary continuing to provide Bathtub Reviews, I Read Reviews, and Dungeon Regular, please consider a one-off donation or becoming a regular supporter of Idle Cartulary on Ko-fi.