I finally picked up Elden Ring on special for an end of year sale, and it has me thinking alot about its design. This post evolved from one post, to three posts, and then I decided it all belonged in one mega-post. I’ll talk about lore in Elden Ring and how it impacts all the interactions you have, I’ll talk about the map itself and how it mimics a specific, interesting style of play, and I’ll talk about how I might apply this as a template to a theoretical hex-crawl.

Part 1: Hostility and lore

In Elden Ring (and in most FromSoft games), everyone wants to kill you.

If you haven’t played it, here’s how it works: You walk around a huge world, and you are marked as an exile, “tarnished”. There are many factions in the world, most at war with each other, but all of which want to kill you, and other tarnished like you. There are a small number of friendly faces, all exiled members of these factions or tarnished themselves, and merchants, that won’t try to kill you.

Thi] complex hostility is really compelling. Knowing everything, anywhere can and wants to kill you makes the world more opaque to you. In Elden Ring in particular, most of the information is in chats you have with one friendly, or in the titles of great enemies, or in notes you can buy. I’ve talked about bite-sized lore before, and Elden Ring is all bite-sized lore.

There’s some compelling politics in the existence of the tarnished as well: Tarnished once lived in the world, and were banished to a hellish existence in punishment for serving the wrong god. Now they’ve been brought back to life, perhaps again to be punished, perhaps as a last-resort attempt by a god to reclaim her fallen world. The hostile world is a punishment for your sins, or perhaps you’re a punishment for theirs.

I have a long-term project, a world that’s a jail, that keeps dropping off the list because I haven’t been able to get it to actually be compelling in its basic form. But casting the players as resurrected villains of legend, or the descendants of them, doomed to live in a land that they are not a part of, and are hated for simply being in, is compelling to me.

Can we make parties of tarnished work in this context, if I wanted to build a world of exiles? Well, Elden Ring speaks to that as well, in a number of ways. Firstly, it implied that some groups are linked magically together, as defeating parties of enemies rewards you with regaining your vitality and magical power. You can summon allies you’ve met in the world to come to your aid in battle. Your foes are gaining this “party power” when you’re defeated as well, after all, if you return, they’re at full health again.

This, then, makes me feel like a hostile world is possible, and is all the more interesting given a political climate that is strange and complex. You’re not a coloniser, but an exile returned, a criminal, hated for your crimes against the gods. The only people who tolerate you are the blasphemers and those who are hated themselves. You’re there to seek vengeance on those that once wronged you, or your ancestors, and to do so, you must pillage this land full of powerful demigods and their lieutenants for every ounce of power that they have claimed themselves.

Part 2: Size, density and line of sight

This facilitates a unique take on who you are in the world, but how does Elden Ring facilitate an interesting overworld, though, when it’s so hostile? The entire Elden Ring map is 79 square kilometres according to a quick google, which entirely fits into 1 single 6 mile hex. This makes sense; you could walk (not run or ride) without stopping from one edge of the map to the other in a few hours, which is long in videogame time but not long in team life.

I’m enamoured of Atop the Wailing Dunes right now (I promise a review is pending) and it uses 1 square mile subhexes, but doesn’t populate things as densely, as there are only about 3 points of interest in a 36 sub-hex region. Comparatively, Elden Ring and Tears of the Kingdom, the open-world games that I’ve recently played, are astoundingly dense. Hot Springs Island does something similar, with 3 points of interest in 2 mile hexes. Truly in Elden Ring you encounter something every thirty seconds across a potential four-hour walk. This is achieved through a bunch of mechanisms, into which I bring this GOATed post by Sacha. Read the whole thing, but I’m going to quote (here U stands for uniqueness, C stands for complexity, and H stands for hostility):

▲U/▲C/▼H – Towns: A dense location hub; a seat of power, assorted resource vendors, several faction HQs, and taverns.

▲U/▼C/▼H – Scenes: Natural features or dwellings; environmental storytelling, hidden resources and/or NPCs. The opposite of Lairs below. Examples: Groves, clearings, passes, shores, shacks, hamlets, villages…

▲U/▼C/▲H – Lairs: Hostile enemy camps or monster lairs – environmental storytelling, hidden resources and/or NPCs. The opposite of Scenes above. Examples: Enemy camps, monster lairs, occupied forts…

▲U/▲C/▲H – Dungeons: Collection of “dungeon rooms”; highly interactive risk vs reward gameplay. Split between combat, exploration and puzzles. Examples: Dungeons, ruins, mines, caves, tombs, castles…

▼U/▼C/▼H – Utilities: Useful recurring sites; an obvious repeatable role or service, such as transportation, shelter, crafting, information, healing, magical buffs. Examples: Taverns, shrines, stables, hiring halls, hot springs, farms, faction outposts…

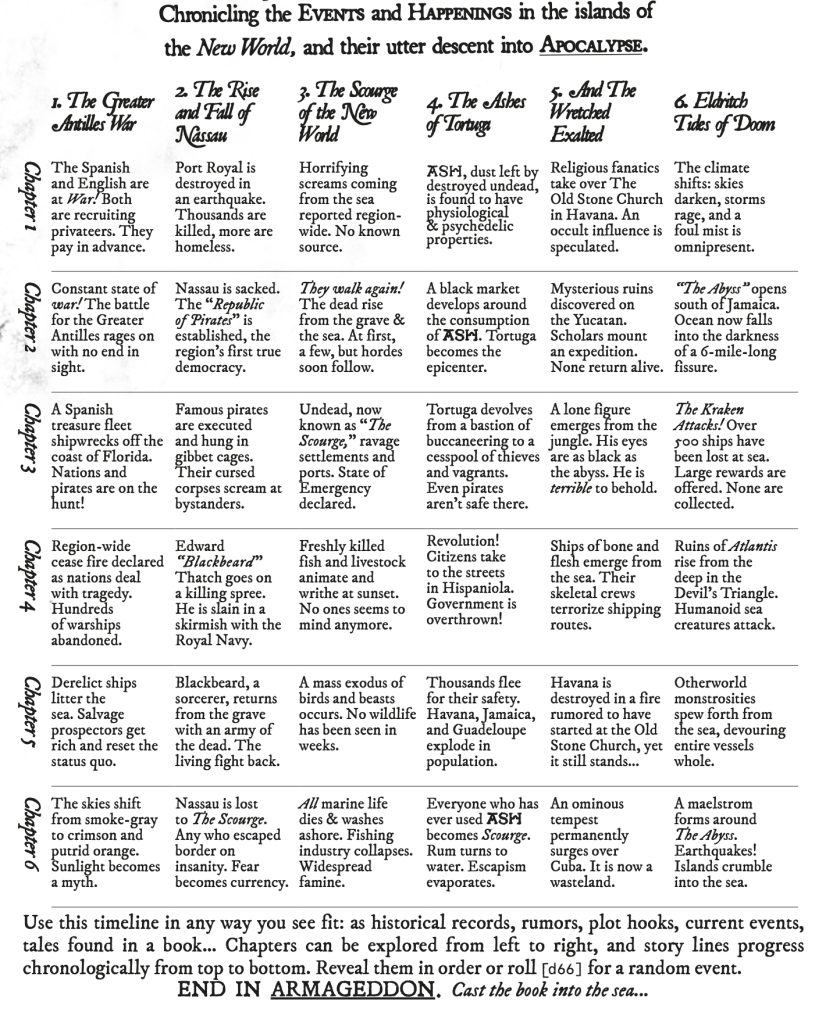

Now, breaking Elden Ring down into these categories (I’ll foreshadow here that I think there are additional categories we can incorporate into our overworlds,but I’ll stick with Sacha’s structure for now):

Elden Ring (541 POIs)

95 Dungeons (divine towers, dungeons, evergaols, legacy dungeons, minor erdtrees, wandering mausoleums – I think I’m right from the design intent here, because there are also 95 stakes or Marika, which indicate significant challenges)

207 Lairs (Bosses, great bosses, or invasions)

203 Scenes (landmarks, sealed areas, telescopes, statues, lore)

41 Utilities (merchants and trainers)

0 Towns (with some exceptions, such as Festivals, which are timed)

The first thing you notice is that Elden Ring has far more points of interest than wither Breath of the Wild or Skyrim, but also that it’s map is far bigger (Skyrim is 37 square kilometers, and Breath of the Wild is 62 square kilometers). The second thing relates to my point on hostility earlier: There are no towns or town-like places at all; all complex interactions are precluded by your outsider status.

Now, I don’t think this is actually a good indicator of how dense the map is, at least in Breath of the Wild and Elden Ring, because one major game activity in both of these is hunting and gathering, for crafting. Always, in eyesight, is something you want to collect or hunt for either body parts or for loot. These are as much a part of the sense of density as all the other points of interest, even though they’re exceedingly minor. They keep you engaged moment-to-moment. There is no list of all enemy encounters in Elden Ring that I’m aware of, but it’s hard to get out of line-of-sight of an enemy unless you’ve already killed everyone you can see from the spot you’re standing in.

Part 3: Line of sight

Breath of the Wild, and Tears of the Kingdom moreso, did a thing where everywhere you stood in the overworld you could see something interesting to investigate. Elden Ring leans even further into this, in two ways: Firstly, the Erd-trees litter the landscape, and you know something cool is there. Secondly, your sites of grace always point you in the direction of nearby plot. Thirdly, the map is a vague in-world document that gives you many vague icons that you have to intuit the meaning of, and even when you don’t have the full map you know where the roads are, so you know where to find the map even if you don’t have details on the environment. Enemies are everywhere, and most common enemies drop common consumables or crafting components when they’re killed; a lot of wild animals are essential to crafting so you need to hunt them. Plant life and other free collectible crafting components literally glow, drawing the eye to them in an otherwise gloomy environment. In these games, level design is really design of line-of-sight. I wouldn’t be surprised if this was literally tested: They had someone walk around the game worlds and make sure there were five things within eyeshot.

But, Elden Ring uses the map to go a step farther, which is that it effectively implements the Landmark, Hidden, Secret formula. That is, there’s always stuff to see; if you use the map and in-world signifiers like enemy locations there’s always stuff to find, and then there are a bunch of environmental secrets that you won’t find without help, off-the-beaten track paths that lead to secret catacombs and dungeons. Every wizard tower is on the map, but most of the catacombs are only found if you follow the shorelines around individually, and it’s taken a bunch of play time for me to realise that I should always check beaches for caves.

Secrets in particular, as alluded to just now, are predictable. All ruins have a basement with a treasure. All mines have elevators. All catacombs have a mechanically locked door that you have to find the lever to open. All towers have a puzzle to solve to open them. And you can subvert these! Boom! The treasure in the basement is a trap! The elevator is broken! The mechanism needs repairing! Non-unique locations allow subversion and allow players to learn things about the world that are useful, and people reuse floor plans and ideas between places.

Part 4: Who cares?

None of this applies to my tabletop RPG, does it? Nah, it does, babe. I’m not going to talk through it all, but I’m going to set some hex-crawl design rules for a theoretical #hex24 sequel to #dungeon23, based on everything above, and drawing from Atop the Wailing Dunes and Sacha’s post.

Rules

- 1 x 3 mile hex per week (all adjacent landmarks are visible from the current hex, as per Joel)

- 1 paragraph description of the terrain

- 3 points of interest (landmark, hidden and secret) of 1 paragraph each

- These are 20% dungeons, 40% lairs, and 40% scenes, with 8/100 chance of being a utility instead (roll each time). And let’s say 1/100 chance of being a town, just to spice things up.

- 1 boss (at one of these points of interest)

- 3 unique rumours (if possible, make these visual, on a map)

- 6 unique ambiences, hazards, discoveries or omens (something is always in sight)

- 6 non-unique wildlife or plantlife (for crafting, wither one of these or one of the previous ones)

- If you don’t want such a hostile world, make one of these previous 12 an NPC.

- Once you’ve written them, go back and add this landmark to the adjacent hexes, so you know what line-of-sight is.

Limitations

- Dungeons match the proposal by Sascha [33% small (5-9 rooms), 54% medium (10-19 rooms), and 13% large (20+ rooms)]

- A small dungeon takes one hex’s work to write, a medium dungeon takes two hex’s work to write, and a large dungeon takes three hex’s work to write. Don’t try to write hexes and dungeons at the same time.

- If god-forbid you roll a town, the same rule applies as for dungeons, and each room counts as a location description.

- Repeat non-unique things between neighbouring hexes.

- Repeat your design in different location types, and only subvert them occasionally.

Ok, concept expunged. Anyone want to make a #hostilehex24?

Idle Cartulary

Playful Void is a production of Idle Cartulary. If you liked this article, please consider liking, sharing, and subscribing to the Idle Digest Newsletter. If you want to support Idle Cartulary continuing to provide Bathtub Reviews, I Read Reviews, and Dungeon Regular, please consider a one-off donation or becoming a regular supporter of Idle Cartulary on Ko-fi.